How I love to go out hunting on a bright Sunday morning—though it’s not my style to shoot furry/feathery/finny animals. My game is to get up early and stalk a wily factoid.

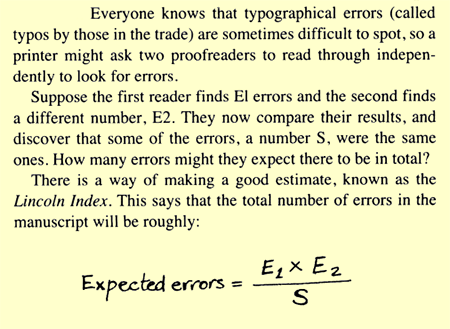

A posting from Mat Roberts, whose blog I’ve recently discovered, sent me out this morning to chase down a passage in How Long Is a Piece of String, a book by Rob Eastaway and Jeremy Wyndham:

The concept here seemed familiar, but the term “Lincoln Index” was new to me. Lincoln who? What index?

Google offered some useful clues. (Also a generous helping of false scents—books about Honest Abe that happen to have an index.) Without even clicking on a link I had the general context:

The Lincoln Index provides a way to measure population sizes of individual animal species. It is based on a capture/mark/ recapture method…

So we’re talking ecology and population biology. The original idea was not to catch the same typo twice but to catch the same furry/feathery/finny creature twice. Interesting. However, the first couple of web pages that Google sent me to (here and here) told me nothing about Lincoln. And, oddly, I found no Wikipedia entry for “Lincoln Index.” If it’s not in Wikipedia, does it exist?

With a little more poking around, I stumbled upon another clue that seemed promising: a mention of “the Lincoln-Pearson equation for estimating population size.” I was still in the dark about Lincoln, but Pearson is quite a familiar figure. Surely that’s Karl Pearson, the pioneering statistician, who did much of his work in the biological sciences and might very well have come up with a scheme for estimating population sizes.

Back at Google, though, searching for “Lincoln-Pearson” turned up nothing pertinent other than the page I’d come from (though I did learn that Karl Pearson “read in chambers in Lincoln’s Inn” during his early years studying law).

More beating the bushes. Eventually I realized I had wandered into a blind alley. Somebody needs to hire a pair of proofreaders: The formula is not “Lincoln-Pearson” but “Lincoln-Petersen.” Try those names at Google and you’ll get an abundance of useful pointers. (You’ll also learn that Abraham Lincoln died in Petersen’s Boarding House, across the street from Ford’s Theater. Google is not just a search engine but also a coincidence engine.)

The particular web page where I finally got the correct names (notes for a course at North Carolina State University) explains that capture-mark-recapture methods

are used extensively to estimate populations of fish, game animals, and many non-game animals. The approach was first used by Petersen (1896) to study European plaice in the Baltic Sea and later proposed by Lincoln (1930) to estimate numbers of ducks. Petersen’s and Lincoln’s method is often referred to as the Lincoln-Petersen Index, even though it is not an index but a method to estimate actual population sizes. (Should it not be the Petersen-Lincoln Estimate?)

I decided to pursue Petersen first—and immediately ran into a few further bibliographic brambles. Some citations spell the name “Petersen” and others “Peterson.” Some give the initials “C. G. T.” and others “C. G. J.” or “C. J. G.” The date might be 1895 or 1896 or 1897. Here’s what I believe to be a correct citation:

Petersen, C. G. J. 1896. The yearly immigration of young plaice into the Limfjord from the German Sea. Report of the Danish Biological Station to the Home Department 6:1–48.

Wikipedia identifies our elusive author as Carl Georg Johannes Petersen (1860-1928). He was a founder of the Danish Biological Station, which was not in fact a station but a mobile laboratory—a decommissioned naval vessel that was moved around from year to year. In 1895, Petersen took the station to the Limfjord, a chain of bays, lakes and channels cutting across the Jutland peninsula in northern Denmark. There he studied the plaice fishery. (Back to Wikipedia: “The European plaice is a right-eyed flounder belonging to the Pleuronectidae family.” But let’s not get started on right-eyed and left-eyed flatfish, or we’ll never get to the end of this.)

Petersen’s report is available online, scanned from a copy belonging to the library of the Marine Biological Laboratory and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and hosted by the Biodiversity Heritage Library of the Internet Archive. A second surprise: The report is written in English. But on reading through it I find only vague and murky connections between the work Petersen reports and the mark-recapture method of estimating populations. There’s nothing resembling the E1E2/S formula.

Petersen does describe a series of capture/mark/recapture experiments. A few hundred plaice were caught and marked by attaching numbered buttons, then put back in the water. Fishermen who recaught the labeled fish in later months were asked to report them. But the purpose of this study was not to estimate the total population; instead, Petersen used before-and-after measurements of the marked fish to estimate their growth rate.

In a much larger experiment, some 82,580 plaice (somebody must have counted them!) were transplanted into the fjord, and 10,900 of the fish were marked by having a hole punched in their dorsal fin. The number of marked fish was recorded as the plaice were caught during the coming year. It’s not clear whether the aim of this project was to estimate the total population, but in any case it didn’t work. The fraction of marked fish in the transplanted batch was about 1/7, but the marked fraction in the subsequent catches was 1/5. Petersen remarks, “This result is very strange,” and I have to agree.

When Petersen did try to estimate the plaice population, he didn’t rely on a recapture scheme. He went out with seine nets designed to dredge up every bottom fish in a measured plot, then extrapolated from the density of fish per unit area.

The whole report is fascinating fishy stuff, but it leaves me wondering just how Petersen came to be given credit for the resampling idea. As far as I can tell, it’s not to be found in this paper.

Having chased down Petersen, I turned back to Mr. Lincoln. Without much trouble I was able to identify the work in question:

Lincoln, F. C. 1930. Calculating waterfowl abundance on the basis of banding returns. United States Department of Agriculture Circular 118:1–4.

The author was Frederick C. Lincoln, who was bird-bander-in-chief in the U.S. for some 25 years. The agency he founded has since migrated from the Department of Agriculture to the U.S. Geological Survey and become the Bird Banding Laboratory.

The author was Frederick C. Lincoln, who was bird-bander-in-chief in the U.S. for some 25 years. The agency he founded has since migrated from the Department of Agriculture to the U.S. Geological Survey and become the Bird Banding Laboratory.

Google returns hundreds of works that cite Lincoln’s paper (including some quite far afield from population biology). But tracking down the USDA document itself was not so easy. If the USDA has it online, I wasn’t able to locate it. But a search of WorldCat eventually turned up an archive in the Hathi Trust Digital Library where you can page through Lincoln’s pamphlet in a copy scanned by Google at the University of Minnesota library.

Lincoln gives only a brief and informal account of the recapture idea, but the basic principle is stated clearly enough:

If in one season 5,000 ducks were banded and yielded 600 first-season returns, or 12 percent, and if during that same season the total number of ducks killed and reported by sportsmen was about 5,000,000, then this number would be equivalent to approximately 12 per cent of the waterfowl population for that year, which would be about 42,000,000.

It’s not hard to translate this formula from the language of duck hunters into the language of proofreaders. The first reader finds 5,000 typos and the second spots 5 million; 600 of these errors are common to both lists, and so the total number of typos is:

![]()

So that’s my reward for a morning spent out hunting: 42 million typos.

Does Frederick Lincoln deserve credit for the Lincoln Index? I’d say he has a good claim, except that Pierre Simon de Laplace had the same idea more than a century earlier. In 1802 Laplace applied his method to estimating the (human) population of France. But maybe that’s a story for another Sunday morning.

Epilogue. This is not really a story about typos, or about fish and ducks. It’s about finding things—about the phenomenal ease of chasing facts on the world wide web. Does a marked fish have any hope of escaping recapture there?