Abstraction is an abstraction. You can’t touch it or taste it or photograph it. You can barely talk about it without resorting to metaphors and analogies. Yet this ghostly concept is an essential tool in both mathematics and computer science. Oddly, it seems to inspire quite different feelings and responses in those two fields. I’ve been wondering why.

In mathematics abstraction serves as a kind of stairway to heaven—as well as a test of stamina for those who want to get there.

![]() and you eat

and you eat ![]() , you will have only

, you will have only ![]() left. After absorbing this bitter truth, you are invited to climb the stairs of abstraction as far as the first landing, where you replace the tasty tangible jelly beans with sugar-free symbols: \(5 - 3 = 2\).

left. After absorbing this bitter truth, you are invited to climb the stairs of abstraction as far as the first landing, where you replace the tasty tangible jelly beans with sugar-free symbols: \(5 - 3 = 2\).

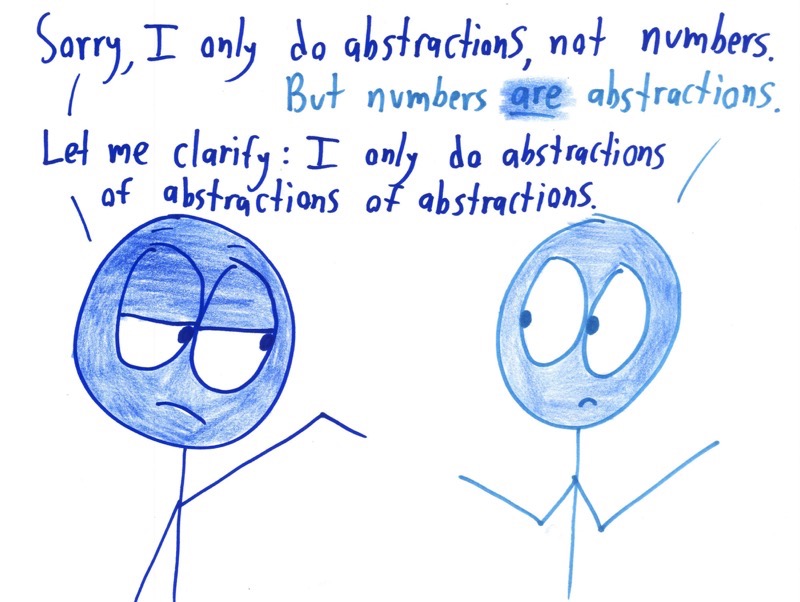

Some years later you reach higher ground. The symbols representing particular numbers give way to the \(x\)s and \(y\)s that stand for quantities yet to be determined. They are symbols for symbols. Later still you come to realize that this algebra business is not just about “solving for \(x\),” for finding a specific number that corresponds to a specific letter. It’s a magical device that allows you to make blanket statements encompassing all numbers: \(x^2 - 1 = (x + 1)(x - 1)\) is true for any value of \(x\).

Continuing onward and upward, you learn to manipulate symbolic expressions in various other ways, such as differentiating and integrating them, or constructing functions of functions of functions. Keep climbing the stairs and eventually you’ll be introduced to areas of mathematics that openly boast of their abstractness. There’s abstract algebra, where you build your own collections of numberlike things: groups, fields, rings, vector spaces.

Not everyone is filled with admiration for this Jenga tower of abstractions teetering atop more abstractions. Consider Andrew Wiles’s proof of Fermat’s last theorem, and its reception by the public. The theorem, first stated by Pierre de Fermat in the 1630s, makes a simple claim about powers of integers: If \(x, y, z, n\) are all integers greater than \(0\), then \(x^n + y^n = z^n\) has solutions only if \(n \le 2\). The proof of this claim, published in the 1990s, is not nearly so simple. Wiles (with contributions from Richard Taylor) went on a scavenger hunt through much of modern mathematics, collecting a truckload of tools and spare parts needed to make the proof work: elliptic curves, modular forms, Galois groups, functions on the complex plane, L-series. It is truly a tour de force.

Is all that heavy machinery really needed to prove such an innocent-looking statement? Many people yearn for a simpler and more direct proof, ideally based on methods that would have been available to Fermat himself.

Almost all of this grumbling about illegimate methods and excess complexity comes from outside the community of research mathematicians. Insiders see the Wiles proof differently. For them, the wide-ranging nature of the proof is actually what’s most important. The main accomplishment, in this view, was cementing a connection between those far-flung areas of mathematics; resolving FLT was just a bonus.

Yet even mathematicians can have misgivings about the intricacy of mathematical arguments and the ever-taller skyscrapers of abstraction. Jeremy Gray, a historian of mathematics, believes anxiety over abstraction was already rising in the 19th century, when mathematics seemed to be “moving away from reality, into worlds of arbitrary dimension, for example, and into the habit of supplanting intuitive concepts (curves that touch, neighboring points, velocity) with an opaque language of mathematical analysis that bought rigor at a high cost in intelligibility.”

I like to imagine abstraction (abstractly ha ha ha) as pulling the strings on a marionette. The marionette, being “real life,” is easily accessible. Everyone understands the marionette whether it’s walking or dancing or fighting. We can see it and it makes sense. But watch instead the hands of the puppeteers. Can you look at the hand movements of the puppeteers and know what the marionette is doing?… Imagine it gets worse. Much, much worse. Imagine that the marionettes we see are controlled by marionettoids we don’t see which are in turn controlled by pre-puppeteers which are finally controlled by actual puppeteers.

Keep all those puppetoids in mind. I’ll be coming back to them, but first I want to shift my attention to computer science, where the towers of abstraction are just as tall and teetery, but somehow less scary.

Suppose your computer is about to add two numbers…. No, wait, there’s no need to suppose or imagine. In the orange panel below, type some numbers into the \(a\) and \(b\) boxes, then press the “+” button to get the sum in box \(c\). Now, please describe what’s happening inside the machine as that computation is performed.

You can probably guess that somewhere behind the curtains there’s a fragment of code that looks like c = a + b. And, indeed, that statement appears verbatim in the JavaScript program that’s triggered when you click on the plus button. But if you were to go poking around among the circuit boards under the keyboard of your laptop, you wouldn’t find anything resembling that sequence of symbols. The program statement is a high-level abstraction. If you really want to know what’s going on inside the computing engine, you need to dig deeper—down to something as tangible as a jelly bean.

How about an electron? c = a + b by tracing the motions of all the electrons (perhaps \(10^{23}\) of them) through all the transistors (perhaps \(10^{11}\)).

To understand how electrons are persuaded to do arithmetic for us, we need to introduce a whole sequence of abstractions.

- First, step back from the focus on individual electrons, and reformulate the problem in terms of continuous quantities: voltage, current, capacitance, inductance.

- Replace the physical transistors, in which voltages and currents change smoothly, with idealized devices that instantly switch from totally off to fully on.

- Interpret the two states of a transistor as logical values (true and false) or as numerical values (\(1\) and \(0\)).

- Organize groups of transistors into “gates” that carry out basic functions of Boolean logic, such as and, or, and not.

- Assemble the gates into larger functional units, including adders, multipliers, comparators, and other components for doing base-\(2\) arithmetic.

- Build higher-level modules that allow the adders and such to be operated under the control of a program. This is the conceptual level of the instruction-set architecture, defining the basic operation codes (add, shift, jump, etc.) recognized by the computer hardware.

- Graduating from hardware to software, design an operating system, a collection of services and interfaces for abstract objects such as files, input and output channels, and concurrent processes.

- Create a compiler or interpreter that knows how to translate programming language statements such as

c = a + binto sequences of machine instructions and operating-system requests.

From the point of view of most programmers, the abstractions listed above represent computational infrastructure: They lie beneath the level where you do most of your thinking—the level where you describe the algorithms and data structures that solve your problem. But computational abstractions are also a tool for building superstructure, for creating new functions beyond what the operating system and the programming language provide. For example, if your programming language handles only numbers drawn from the real number line, you can write procedures for doing arithmetic with complex numbers, such as \(3 + 5i\). (Go ahead, try it in the orange box above.) And, in analogy with the mathematical practice of defining functions of functions, we can build compiler compilers and schemes for metaprogramming—programs that act on other programs.

In both mathematics and computation, rising through the various levels of abstraction gives you a more elevated view of the landscape, with wider scope but less detail. Even if the process is essentially the same in the two fields, however, it doesn’t feel that way, at least to me. In mathematics, abstraction can be a source of anxiety; in computing, it is nothing to be afraid of. In math, you must take care not to tangle the puppet strings; in computing, abstractions are a defense against such confusion. For the mathematician, abstraction is an intellectual challenge; for the programmer, it is an aid to clear thinking.

Why the difference? How can abstraction have such a friendly face in computation and such a stern mien in math? One possible answer is that computation is just plain easier than mathematics.

Another possible explanation is that computer systems are engineered artifacts; we can build them to our own specifications. If a concept is just too hairy for the human mind to master, we can break it down into simpler pieces. Math is not so complaisant—not even for those who hold that mathematical objects are invented rather than discovered. We can’t just design number theory so that the Riemann hypothesis will be true.

But I think the crucial distinction between math abstractions and computer abstractions lies elsewhere. It’s not in the abstractions themselves but in the boundaries between them.

Mathematics also has its abstraction barriers, although I’ve never actually heard the term used by mathematicians. A notable example comes from Giuseppe Peano’s formulation of the foundations of arithmetic, circa 1900. Peano posits the existence of a number \(0\), and a function called successor, \(S(n)\), which takes a number \(n\) and returns the next number in the counting sequence. Thus the natural numbers begin \(0, S(0), S(S(0)), S(S(S(0)))\), and so on. Peano deliberately refrains from saying anything more about what these numbers look like or how they work. They might be implemented as sets, with \(0\) being the empty set and successor the operation of adjoining an element to a set. Or they could be unary lists: (), (|), (||), (|||), . . . The most direct approach is to use Church numerals, in which the successor function itself serves as a counting token, and the number \(n\) is represented by \(n\) nested applications of \(S\).

From these minimalist axioms we can define the rest of arithmetic, starting with addition. In calculating \(a + b\), if \(b\) happens to be \(0\), the problem is solved: \(a + 0 = a\). If \(b\) is not \(0\), then it must be the successor of some number, which we can call \(c\). Then \(a + S(c) = S(a + c)\). Notice that this definition doesn’t depend in any way on how the number \(0\) and the successor function are represented or implemented. Under the hood, we might be working with sets or lists or abacus beads; it makes no difference. An abstraction barrier separates the levels. From addition you can go on to define multiplication, and then exponentiation, and again abstraction barriers protect you from the lower-level details. There’s never any need to think about how the successor function works, just as the computer programmer doesn’t think about the flow of electrons.

The importance of not thinking was stated eloquently by Alfred North Whitehead, more than a century ago:

Alfred North Whitehead, An Introduction of Mathematics, 1911, pp. 45–46. It is a profoundly erroneous truism, repeated by all copybooks and by eminent people when they are making speeches, that we should cultivate the habit of thinking of what we are doing. The precise opposite is the case. Civilisation advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking about them. Operations of thought are like cavalry charges in a battle—they are strictly limited in number, they require fresh horses, and must only be made at decisive moments.

If all of mathematics were like the Peano axioms, we would have a watertight structure, compartmentalized by lots of leakproof abstraction barriers. And abstraction would probably not be considered “the hardest part about math.” But, of course, Peano described only the tiniest corner of mathematics. We also have the puppet strings.

In Piper Harron’s unsettling vision, the puppeteers high above the stage pull strings that control the pre-puppeteers, who in turn operate the marionettoids, who animate the marionettes. Each of these agents can be taken as representing a level of abstraction. The problem is, we want to follow the action at both the top and the bottom of the hierarchy, and possibly at the middle levels as well. The commands coming down from the puppeteers on high embody the abstract ideas that are needed to build theorems and proofs, but the propositions to be proved lie at the level of the marionettes. There’s no separating these levels; the puppet strings tie them together.

In the case of Fermat’s Last Theorem, you might choose to view the Wiles proof as nothing more than an elevated statement about elliptic curves and modular forms, but the proof is famous for something else—for what it tells us about the elementary equation \(x^n + y^n = z^n\). Thus the master puppeteers work at the level of algebraic geometry, but our eyes are on the dancing marionettes of simple number theory. What I’m suggesting, in other words, is that abstraction barriers in mathematics sometimes fail because events on both sides of the barrier make simultaneous claims on our interest.

In computer science, the programmer can ignore the trajectories of the electrons because those details really are of no consequence. Indeed, the electronic guts of the computing machinery could be ripped out and replaced by fluidic devices or fiber optics or hamsters in exercise wheels, and that brain transplant would have no effect on the outcome of the computation. Few areas of mathematics can be so cleanly floated away and rebuilt on a new foundation.

Can this notion of leaky abstraction barriers actually explain why higher mathematics looks so intimidating to most of the human population? It’s surely not the whole story, but maybe it has a role.

In closing I would like to point out an analogy with a few other areas of science, where problems that cross abstraction barriers seem to be particularly difficult. Physics, for example, deals with a vast range of spatial scales. At one end of the spectrum are the quarks and leptons, which rattle around comfortably inside a particle with a radius of \(10^{-15}\) meter; at the other end are galaxy clusters spanning \(10^{24}\) meters. In most cases, effective abstraction barriers separate these levels. When you’re studying celestial mechanics, you don’t have to think about the atomic composition of the planets. Conversely, if you are looking at the interactions of elementary particles, you are allowed to assume they will behave the same way anywhere in the universe. But there are a few areas where the barriers break down. For example, near a critical point where liquid and gas phases merge into an undifferentiated fluid, forces at all scales from molecular to macroscopic become equally important. Turbulent flow is similar, with whirls upon whirls upon whirls. It’s not a coincidence that critical phenomena and turbulence are notoriously difficult to describe.

Biology also covers a wide swath of territory, from molecules and single cells to whole organisms and ecosystems on a planetary scale. Again, abstraction barriers usually allow the biologist to focus on one realm at a time. To understand a predator-prey system you don’t need to know about the structure of cytochrome c. But the barriers don’t always hold. Evolution spans all these levels. It depends on molecular events (mutations in DNA), and determines the shape and fate of the entire tree of life. We can’t fully grasp what’s going on in the biosphere without keeping all these levels in mind at once.