If you were an astute or lucky stock trader on the afternoon of May 6, you could have bought shares of Accenture PLC for a penny each and sold them a minute later for almost $40. Or you could have invested in Sotheby’s for about $30 a share and, if your timing was right, sold out at a price of $99,999.9999. Did you miss those moneymaking opportunities? Don’t kick yourself too hard. Those particular trades were canceled by the exchanges as “clearly erroneous errors.” But millions of other bizarre transactions were allowed to stand, even though prices were fluctuating wildly.

A preliminary report on these events was released last week by a joint committee of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission and the Securities and Exchange Commission. The report reads a lot like an inquiry into an airplane crash, evoking both horror and fascination. But whereas the investigators of aircraft accidents usually come up with a likely cause, the CFTC/SEC committee makes clear that they don’t yet understand what happened on May 6, and it seems possible we’ll never know.

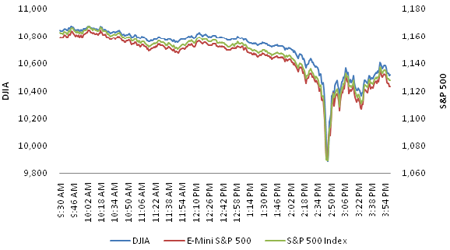

Throughout that day, stock prices were trending lower, a decline attributed mainly to worries about the European economy. But those concerns can’t account for the extraordinary crevasse the market fell into and then climbed out of between 2:30 and 3:00 p.m. The Dow Jones Industrial Average (blue) and the Standard and Poor’s 500 index (green) both lost 6 or 7 percent of their value in less than 10 minutes, then gained it all back. If those price changes are extrapolated to all U.S. stocks, something like a trillion dollars went missing for half an hour. (The red line in the graph, labeled E-Mini S&P 500, refers to a stock futures contract, which I’ll discuss below.)

What could cause such rapid whipsawing? The first speculations implicated a “fat-finger trade”—a data-entry error. There have been several such events in recent years; for example, in 2005 a Japanese broker who meant to sell 1 share of stock at a price of 610,000 yen keyed in instructions to sell 610,000 shares at 1 yen. However, the committee finds no evidence of such goofs on May 6.

The committee also dismisses the Procter & Gamble theory, put forward by commentators on CNBC who noticed a particularly sharp break in the stock of that company (one of the 30 Dow components).

The decline in PG did not begin until 2:44 p.m., well after the broader market indices, which began their precipitous drop at approximately 2:40 p.m. Accordingly, early reports that an inordinately large trade in PG may have triggered the broad market decline do not appear well founded.

Various kinds of deliberate mischief have also been mentioned as possible causes. Maybe some secretive hedge fund has found a way to manipulate the market to its own advantage. Or a hacker might have infiltrated the computer networks that handle stock transactions. The glitch could even be an act of international terrorism. Again, the committee finds no signs of such malevolence but can’t entirely rule out the possibility.

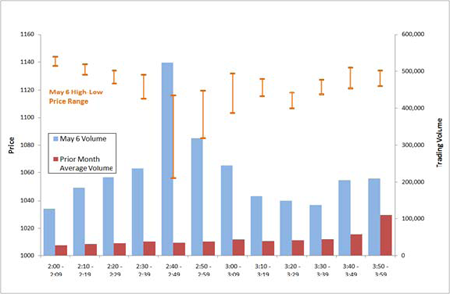

The committee gives closer scrutiny to high-volume trading on the stock futures market, and in particular to the E-Mini S&P 500 futures, which offer a mechanism for betting on the value of the S&P 500 index a few weeks in the future. Traffic in S&P 500 futures was unusually heavy on May 6, and it spiked at the time of the big dip:

The price excursions were wide enough to trigger a “Stop Logic” system that halted trading for five seconds. Furthermore, transactions initiated by a single firm accounted for some 9 percent of the trading volume in the critical half-hour, and all of that firm’s activity was on the selling side. (The committee report does not name this firm, but others have identified it as Waddell & Reed, a mutual fund in Overland Park, Kansas.) So, do we blame it all on a mutual fund run amok in the KC suburbs? The committee thinks further investigation is warranted, but they also note that the same firm has made similar trades in the past, as have many other parties, all without causing a ripple in the wider market.

Two more items of Wall Street arcana that get a lot of attention in the report are stop-loss orders and stub quotes. A stop-loss order causes a stock to be sold automatically if the price falls below a specified threshold. Traders enter such orders in the expectation that the sale will take place at a price near the threshold level, but if prices are falling rapidly, there’s no assurance of that. For a few minutes on May 6, certain stop-loss orders had the effect not of stopping losses but of maximizing them. At the instant when the orders were executed, there were no purchase offers at any price higher than a penny, and so that’s the price the stocks sold for. The offers of $0.01 are thought to have been “stub quotes,” placed by brokers who act as market-makers and who are therefore obliged always to have both buy and sell orders in place. Stub quotes are a way of meeting this obligation at times when the broker doesn’t really want to be in the market. Trades are never supposed to be executed at the stub price, but that’s what happens if no one else is buying. (Transactions at $100,000 per share reflect stub quotes at the other end of the scale, for shares that no one else is willing to sell.)

• • •

If the Commodity Futures Trading Commission and the Securities and Exchange Commission don’t know what went wrong on May 6, then I’m sure I don’t know either. But a couple of points seem pretty obvious (which may be why the committee left them unstated).

First, whatever happened on May 6 must have been driven by the internal dynamics of the securities markets, not by events in the larger economy. No changes in the business prospects of Accenture PLC would justify 4,000 percent swings in the company’s market value within half an hour.

Second, there’s got to be some instability at work here—some positive feedback loop. A thousand-point dip in the Dow wasn’t just a freak coincidence, where millions of stockholders acting independently all chose to sell at the same moment, and then a few minutes later changed their minds and decided to buy. Rather, there must have been some mechanism whereby one trader’s decision to buy or sell induced other traders to do the same.

The committee report points out that stop-loss orders create one such destabilizing loop, which is hard-wired into the market machinery. If a stop-loss order on a particular stock is activated at $100, say, the sale of those shares might drive the market price down to $95, triggering more stop-loss orders and lowering the price still further, in a runaway cascade. More generally, any trading strategy that calls for following trends or tracking “market momentum” is susceptible to this kind of instability. For any one individual, selling out when the market sags may or may not be a prudent policy; but if everyone adopts such a rule, the outcome is certain disaster.

Positive feedbacks of some kind surely had a role in the crash of May 6, but they can’t be the whole story. If a wave of self-reinforcing selling accounts for the sudden dive in prices, what explains the equally sudden turnaround and recovery? And there’s an even deeper question. It’s not hard to dream up models in which every random fluctuation is amplified by positive feedback, but the result is an economy that experiences weird jolts and hiccoughs all the time. A useful theory of May 6 has to explain not only what happened on that day but also why it doesn’t happen routinely.

Some analysts have compared the May 6 event with the stock market crash of October 1987, which was even deeper than the recent dip, although it played out over a period of days rather than minutes. I have vivid memories of this event; I followed it on the radio (no CNBC in those days) and then I read the post-mortem reports. But apparently my memory is faulty in certain crucial details. The crash was blamed in large part on “program trading,” which I took to mean that computer programs were making buy and sell decisions in real time. The root of the problem, as I understood it then, was that multiple programs controlling large investments all shared the same basic logic, so that they would all react in the same way to changing market conditions. It turns out, though, that the computing machinery of the time was not up to operating in this online regime. Instead, the economic models were run in batch mode, and the trades were executed after the fact. There were people in the loop.

Today, in contrast, thousands of computers are plugged directly into the markets, and program trading is everywhere. The big hedge funds and other major players install their servers in colocation facilities next door to the major exchanges, as a way of reducing communication latency. For “high frequency traders,” transactions are routinely completed in about a third of a millisecond. From the point of view of these firms, the sudden market collapse on May 6 played out in slow motion. During the 10 minutes of tumbling prices, a trading rate of three transactions per millisecond allows time for 180,000 transactions.

Perhaps, then, the much-feared runaway automation of 1987 has finally caught up with us in 2010. Ironically, though, the CFTC/SEC report hints that if automated trading was behind the May 6 glitch, the problem might not be the presence of these traders but rather their sudden withdrawal from the market. Julie Creswell tells the story in The New York Times:

RED BANK, N.J. — Above the Restoration Hardware in this Jersey Shore town, not far from the Navesink River, lurks a Wall Street giant.

Here, inside the humdrum offices of a tiny trading firm called Tradeworx, workers in their 20s and 30s in jeans and T-shirts quietly tend high-speed computers that typically buy and sell 80 million shares a day.

But on the afternoon of May 6, as the stock market began to plunge in the “flash crash,” someone here walked up to one of those computers and typed the command HF STOP: sell everything, and shutdown.

According to Creswell, high-frequency traders account for between 40 and 70 percent of all the trading volume on U.S. securities markets, so the sudden departure of these market participants would certainly have a noticeable effect.

Almost everything about the stock market has changed utterly in the years since 1987. Back then, trading was done by guys in colorful blazers yelling at one another on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. That trading floor still exists, but it’s a kind of Wall Street theme park, maintained for the benefit of visiting high school classes and CNBC cameras. Most of the actual trading in NYSE stocks is done across the river in Jersey City by electronic ”matching engines” that line up offers to sell with bids to buy. Once there were “specialists” in each stock who were expect to intervene with their own capital to damp out unwarranted price fluctuations. That role has not disappeared entirely, but in most modern markets no one has legal responsibility for maintaining stability. In 1987 most stocks could be bought and sold in only one venue; now, transactions are automatically routed to whatever exchange offers the best terms, including the ominously named “dark pools,” where shares change hands anonymously. Back then, brokerage fees and other transaction costs were high enough to discourage strategies such as high-frequency trading; now there is much less friction in the market. It’s a new world.

Even though the CFTC and the SEC have not yet sorted out the causes of the May 6 blip, they are already proposing remedies. The basic tool is the time out: When the market throws a tantrum, it will be told to sit in the corner for a few minutes. Many such rules already exist, some of them going back to 1987. The rationale is that a pause in trading will allow time for “additional liquidity to enter the market.” In other words, if everyone is selling in a panic, we wait a little while for some buyers to show up. Of course the pause might also allow time for more sellers to join the stampede.

A year ago, I was writing about the uneasy relations between economics and the engineering discipline known as control theory. That was in the context of macroeconomics, where the aim is to control cycles of boom and bust with a time scale of years or decades. The challenges of controlling securities markets are rather different: The time scale is much shorter, which means you have to act quicker, but on the other hand it’s much easier to measure what’s happening, to gather information second by second. But the biggest impediment to effective control is the same in both cases: It’s hard to control the dynamics of a system when you don’t understand those dynamics—when you can’t reliably predict what the system will do in the absence of control or how it will respond to control actions. Given the human element in economic affairs—including the likely presence of actors who will try to subvert any control strategy—it’s not clear that we can ever have that kind of predictive power.

Great summary