Beyond digital photography lies computational photography, which holds out the promise of extracting more bits from every photon. When I wrote about this idea a few years ago, I had no hands-on experience with computational cameras. The first widely available “light-field camera,” called the Lytro, was announced last fall. Mine finally arrived last week. So far I’ve taken only a few dozen pictures, so this is a very preliminary report. But the camera itself is a very preliminary product, so perhaps it’s appropriate to treat it as a preview of things to come.

Here are a couple of pictures to play with. First, more magnet balls, with evidence that I’ve finally figured out how to stack them up in something resembling a hexagonal close-packed configuration.

And some flowers, which seem to be the front-running subject matter for Lytro photos. These are orchids at a street-corner stand, with extra inventory on display for mother’s day.

I trust that you’ve figured out the trick: Clicking on a point in the image refocuses on the depth of the scene at that point. (You can also double-click to zoom.)

How is this magic accomplished? The Stanford doctoral dissertation of Ren Ng sets forth the basic idea. Ng is the founder and CEO of Lytro Inc.

This dissertation introduces a new approach to everyday photography, which solves the longstanding problems related to focusing images accurately. The root of these problems is missing information. It turns out that conventional photographs tell us rather little about the light passing through the lens. In particular, they do not record the amount of light traveling along individual rays that contribute to the image. They tell us only the sum total of light rays striking each point in the image. To make an analogy with a music-recording studio, taking a conventional photograph is like recording all the musicians playing together, rather than recording each instrument on a separate audio track.

In this dissertation, we will go after the missing information. With micron-scale changes to its optics and sensor, we can enhance a conventional camera so that it measures the light along each individual ray flowing into the image sensor. In other words, the enhanced camera samples the total geometric distribution of light passing through the lens in a single exposure. The price we will pay is collecting much more data than a regular photograph. However, I hope to convince you that the price is a very fair one for a solution to a problem as pervasive and long-lived as photographic focus. In photography, as in recording music, it is wise practice to save as much of the source data as you can.

So we have a radically different kind of camera here. It has a lens, but there’s no focusing ring. Focusing is left to the computational post-processing of the image.

The after-the-fact refocusing is most dramatic in close-up shots, with a wide ratio between the distances of near and far objects. You can see the effect by clicking around in this image of pine tree putting out some exuberant spring growth.

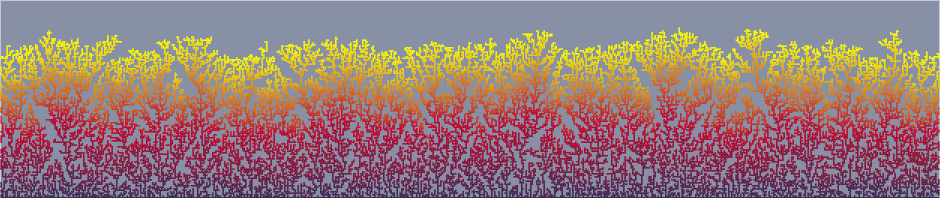

The camera is capable of coming in even closer, as in this macro shot of some lichens and mosses on rocks in western Massachusetts. (The gray stalks are wo or three millimeters tall.)

Getting much of a focal range is harder when you’re dealing with more distant subjects. This was my best attempt to catch a red-wing blackbird in a marsh below Danehy Park in Cambridge.

When you pull back even farther, the camera optics have enough depth of field that everything is in focus at once. Ordinarily, that high depth of field would be a virtue, but it strangely takes the fun out of Lytro pictures.

The gallery on the Lytro web site includes lots more examples, including some classic pull-focus tricks like spider webs and raindrops on windowpanes.

• • •

Just a few years ago, the immediate reaction to the Lytro camera would have been: “How do you refocus after you print your pictures? You can’t click on paper.” Times change. The Lytro makes more sense in an age when people share their pictures on Facebook or Twitter instead of printing and framing them. Yet I still have misgivings about Lytro’s scheme for distributing and publishing images. The Lytro photographs displayed above are not hosted on bit-player.org, as this text is; they are embedded <iframe> tags, providing a window onto content hosted at lytro.com. That’s the only way I can post them here. This is an annoyance to a curmudgeonly control freak like me; I want to retain possession of my own work, as well as control its presentation.

There is no fundamental reason the images have to be hosted at lytro.com. The refocusing algorithms are not running on the Lytro servers. What’s embedded in the iframes is essentially a stack of images with different focal points, along with a Flash application that responds to clicks by displaying the appropriate image from the stack. (The use is Flash is another annoyance. Lytro evidently has a non-Flash version of the software, since the photos are viewable with Flashless devices such as the iPad, but there’s no readily accessible way to choose the non-Flash version on other platforms.)

The camera itself has an unconventional tubular design, but it fits the hand well enough and has a satisfying heft and solidity. The only physical controls are power, zoom and the shutter botton. The one severe problem with the camera hardware is that the viewing screen is too small (1 square inch) and too coarse; also, it’s useless in bright sunlight. Often, you can’t see what you’re about to photograph, and afterwards you can’t see what you’ve captured until you upload the image to a computer.

The software that runs on the computer has its own issues. For now it is Macintosh-only; a Windows version is promised, but there’s no mention of Linux. When importing images, the software hogs the CPU, setting off a tremendous whoosh of fan noise. And once you have the images loaded into the software, there’s not actually much you can do with them, other than add metadata or send them to the Lytro web site. There are no tools for cropping, correcting colors, sharpening, etc. You can export a JPEG version, but it’s of course merely a static pixel array. (The JPEGs are 1080 by 1080 pixels, with quality in the range you’d expect from a good cell-phone camera.)

The full light-field photos are stored in 16-megabyte “.lfp” files, but there’s no public documentation on the format of those files. As far as I know, no software other than Lytro’s own can read the files. If there are any plans for, say, a Photoshop plugin or a software development kit, they are not discussed publicly.

Is the Lytro the first chapter in the future of photography, or a novelty that will fade after a year or two? I suspect the answer will depend on how quickly Lytro is able to develop and release new features for the software and new models of the camera. At the moment, what the camera offers is a single trick: focusing after rather than before you press the shutter button. It’s a neat trick, but probably not neat enough to support a whole new photographic infrastructure. The light-field technique could offer more. Lytro has promised that a future version of the software will allow control not just of focus but of depth of field, so that you can choose a version of the image in which everything is in focus at once. There are still more possibilities, even including shifting the camera’s apparent point of view after the picture is taken. But it remains to be seen whether such features can be brought to market before people lose patience or interest.

Every new technology looks clumsy and toy-ish at first. Nobody wanted the telephone or the lightbulb from day zero — but those technologies improved at an amazing rate, greatly exceeding initial expectations.

I think this, if it’s any worth, will eventually follow the same road. As incomplete a product as it looks now, it may become the de-facto way of taking pictures, just as the telephone became the standard means for communication and the lightbulb replaced burning lights.

This is an amazing innovation! It makes all previous photo technology instantly obsolete. Bravo!

It seems the lfp format is actually quite straightforward to unpack, there is a discussion here: http://eclecti.cc/computervision/reverse-engineering-the-lytro-lfp-file-format and a tool for unpacking here: https://github.com/nrpatel/lfptools

These pictures just blow me away.

I’m not a photorapher, I’m a musician, so I can relate to your explanation that it is more like recording each instrument separately in the studio.

I love the after-the-fact processing of the focus. Such a cool idea and something I had never even considered before.

Just how big are these images though? I’m guessing up in the 20-30mb range? Or am I way off base here???

Really cool stuff…

Martin.

The full-size .lfp files are 16 megabytes. The flattened JPEG versions are less than a megabyte.