Oh, the Places I’ve Been!

by Brian Hayes

Published 11 May 2011

When I heard the rumors that my iPhone was tracking my movements and keeping a log of location data, I was annoyed. Now that Apple has fixed this bug/feature, I’m even more annoyed. There’s just no pleasing me.

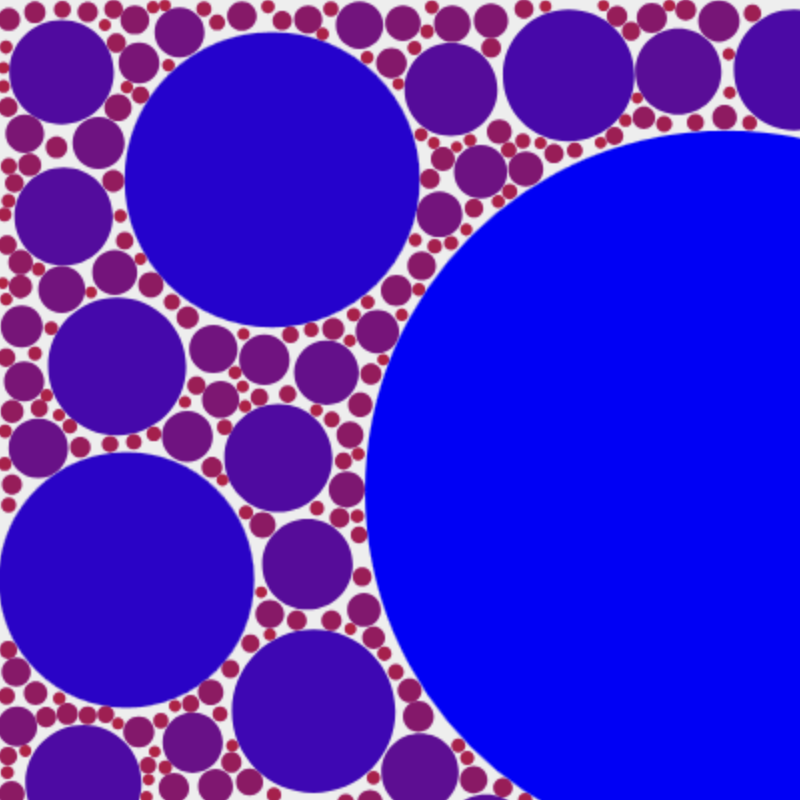

The fuss began three weeks ago, when Alasdair Allan and Pete Warden announced at a conference that iPhones record a location fix every few seconds, based on position with respect to cell-phone towers and wifi access points. The log file is saved on the phone, they said, and also transferred to any computer the phone syncs with, in the form of an SQLite database named “consolidated.db.” Allan and Warden wrote a handy Macintosh application, iPhoneTracker, that extracts the geographical markers and displays them on a map. At left is the record of a trip I took last summer through northern California and southern Oregon, as traced by cell phone towers along the way. There are lots of mysteries and spurious details among those dots, but the broad outline of the route is displayed clearly enough: a counterclockwise loop up I-5, across the Cascades to Coos Bay, and back down to San Francisco on U.S. 101.

Here’s another map-pin travel diary, a memento of a brief visit to Pittsburgh for a meeting at Carnegie Mellon:

In this case the dots represent wifi hotspots rather than cell-phone towers. Lots of hotspots! They look like a swarm of bees. The cluster at lower left is the CMU campus, where the meeting was held. Moving northeast, the nearest clump of dots is the vicinity of my hotel. The rest of the dots, further north and east, trace the routes of a couple of walks I took, out looking for dinner. Curiously, a third long walk doesn’t show up at all, even though I had the phone with me, and indeed used the Maps app to get unlost a couple of times.

(I should mention that the version of iPhoneTracker distributed by Allan and Warden does not show wifi locations, and it plots cell towers on a rather coarse grid. But the software is open-source, and those limitations are undone with a couple of easy edits.)

Allan and Warden’s discovery of the iPhone location database wasn’t exactly new. Alex Levinson reported some months ago on an earlier version of the location log. And last July Apple explained its “location services” privacy policies in considerable detail in response to an inquiry from two Senators. No one took much notice of those earlier reports, but the new one caused a ruckus. It soon emerged that Android devices are collecting similar information and sharing it with Google. Yesterday, both Apple and Google were grilled in Congress.

The ruckus has mostly been about quaint 20th-century notions like personal privacy. I have my own worries on that score, but what irks me most is not that my phone is storing this information but that Apple gives me no access to it. If I’m going to help them build an immense database of cell towers and wifi beacons, then surely I should at least be able to retrieve and display my own coordinates, no?

The Allan and Warden program fills this need to some extent. And last week the New York Times bits blog announced a cloud-based approach that might be even better. They are inviting iPhone users to upload their location information to a service called OpenPaths, where you can build animated maps of your own peregrinations and, perhaps, if you choose, share the data for research purposes.

There’s just one problem. Apple’s response to the invasion-of-privacy complaints was to issue an operating system update that will make it even harder—probably impossible—for me to get access to my own data. After I install the update, my phone will not stop collecting geographic information, nor will it stop reporting location fixes to Cupertino, but it will encrypt the file so that I can’t read it. Maximally annoying. Geolocation wthout representation.

As far as I can tell, Apple is telling the truth about the nature and source of the information in consolidated.db. When the story first broke, I assumed—along with many others—that the database was recording the cell sites and wifi networks that my phone detected as I wandered around, carrying the device in my pocket. In other words, the database was a local copy of a location log that was also, presumably, being uploaded to Apple. An Apple press release from April 27 insists that I had it backwards. This is not information gathered by my phone. Instead it is a “crowd-sourced database” downloaded from Apple to my phone.

3. Why is my iPhone logging my location?

The iPhone is not logging your location. Rather, it’s maintaining a database of Wi-Fi hotspots and cell towers around your current location, some of which may be located more than one hundred miles away from your iPhone, to help your iPhone rapidly and accurately calculate its location when requested….

4. Is this crowd-sourced database stored on the iPhone?

The entire crowd-sourced database is too big to store on an iPhone, so we download an appropriate subset (cache) onto each iPhone….

6. People have identified up to a year’s worth of location data being stored on the iPhone. Why does my iPhone need so much data in order to assist it in finding my location today?

This data is not the iPhone’s location data—it is a subset (cache) of the crowd-sourced Wi-Fi hotspot and cell tower database which is downloaded from Apple into the iPhone to assist the iPhone in rapidly and accurately calculating location. The reason the iPhone stores so much data is a bug we uncovered and plan to fix shortly….

Why do I believe this self-serving story? Basically because a true log of the phone’s trajectory through time and space would look rather different from the list of entries I find in consolidated.db. My phone spends much of its time in one place, talking all day to the same wifi links and the same cell towers. A log that recorded my moment-by-moment position over a period of months would include many, many repeated contacts with these few nearby sites. But in fact consolidated.db has exactly one entry for each such site. (The structure of the database guarantees this: The wifi MAC address and the set of identifiers for cell towers are primary keys in the data tables, which means they must be unique.) Another clue: Clumps of sites in the same neighborhood all have exactly the same time stamp. It appears they were all downloaded to the phone at the same time. That’s not the way I would have encountered the sites while walking the streets of the Shadyside neighborhood in Pittsburgh.

All the same, I still insist that I have an ownership stake in this database. I’m part of the crowd that sourced it. Without the unwitting participation of millions of iPhone owners, Apple’s database wouldn’t exist. And a piece of it is stored on my phone—some 24 megabytes’ worth (24,209 cell phone towers, 177,103 wifi routers). Finally, even if the database is not constructed as a direct tabulation of my movements, it provides a remarkably accurate record of the places I’ve been. That too makes the data mine.

Addendum 2011-05-12: Apple and Google argue that if you want the benefits of location-based services, then you have to be willing to share information about your whereabouts. Is this trade-off actually necessary? I think not. If the entire database were resident on the phone, then the phone itself could calculate its position, without any need to reveal that position to the outside world. If the global database is too large to put a copy on every phone, then installing larger pieces of it would at least raise the granularity of the information being leaked. There’s a difference between knowing I was in Pennsylvania and knowing I was at the intersection of Fifth Avenue and South Aiken Avenue in the Shadyside neighborhood of Pittsburgh.

The real need for sending my position information to Apple or Google is not so that I can get the benefit of the cell/wifi database but rather so that I can help them build that database. When Google first set out to compile this kind of information, they did so at their own expense, equipping their Streetview photography cars with wifi and cell antennas. The Skyhook database was created in a similar way. Using cell-phone customers to do the same work changes the terms of the transaction in a way I find unpleasant. I’m contributing to a proprietary database; I’m doing the work of drivers who would otherwise have to be hired to cruise the streets; but I’m not being compensated; on the contrary, I’m paying for the privilege. I can see an argument for a scheme in which we all voluntarily contribute data for a public good, but that’s not the nature of this transaction.

I should point out that there are efforts to build publicly accessible databases of cell and wifi coordinates. There’s Cellspotting, which looks interesting but works only with a few kinds of mobile phones. And there’s OpenBmap, which has some rough edges but even so provides an impressive amount of information. It’s the place to go if you want to learn about the cell towers in your neighborhood and figure out the numbering scheme that identifies them in the consolidated.db file.

Finally, a question: Can we imagine a “zero-knowledge” internet location service? GPS works this way: I can get a fix on my position simply by receiving signals from GPS satellites and doing some arithmetic on them; I don’t have to transmit anything at all. What the satellites are broadcasting is merely a time signal, and the arithmetic I have to do consists in finding a consistent time-of-flight solution for signals from three or four of the satellites. If we had internet beacons of known location broadcasting a continual stream of high-resolution time signals, we could do something similar. A complication is that the internet is a very inhomogeneous medium, where signals move at very different speeds. On the other hand, it would be easy to collect input from hundreds of beacons, rather than three or four satellites. Even without the beacons, the art of inferring latitude and longitude from IP number seems to be pretty highly developed; there’s a fascinating recent paper (PDF) on how it’s done, by Yong Wang and colleagues at Northwestern and Microsoft Research. (The GPS-beacons-on-the-internet idea must have been proposed a zillion times by now, but I don’t have a reference ready at hand.)

Responses from readers:

Please note: The bit-player website is no longer equipped to accept and publish comments from readers, but the author is still eager to hear from you. Send comments, criticism, compliments, or corrections to brian@bit-player.org.

Publication history

First publication: 11 May 2011

Converted to Eleventy framework: 22 April 2025

Of course the phone does send data to Apple/Google etc. to help build their location databases, but the reason that “tracking file” is on your phone has nothing to do with tracking — in fact it’s there to give you better location services. Whenever your phone contacts the location servers, the servers send back a list of towers and hotspots nearby — not necessarily in range right now, but places you might wander to soon. That way if you walk into a cell dead zone and your phone can’t contact the location servers, it can still consult its local DB of beacons that it downloaded earlier and keep providing you a good location.

This is all interesting, and I’m looking forward to checking out the rough locations of my recently acquired iPhone.

A couple of points about your last paragraph; from what I understand, GPS receivers use 4 satellites to calibrate their clocks—since the receiver must know the time very precisely to understand where the satellite was when it emitted it’s signal—so the satellites carry multiply redundant atomic clocks while the receivers carry normal sloppy clocks. (Though maybe with the recent progress in chip-sized atomic clocks this will change?) I’m not sure what the capability (or requirement) of internet hardware to reliably carry accurate time signals is, but it may be a problem?

The other thought that came to mind was homomorphic encryption, which would maybe let you do something like encrypt a query to their database without them having to decrypt the query, or perhaps your identity could be encrypted so they could get your location but not who it came from? Seems like the kind of thing someone somewhere would have researched extensively already…