QCD

by Brian Hayes

Published 19 October 2008

Lattice QCD is something I’ve been trying to understand for 30 years. My latest attempt is chronicled in the new issue of American Scientist.

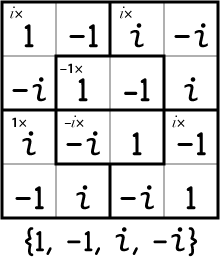

QCD is quantum chromodynamics, the theory of interactions between quarks and gluons. The lattice version of the theory appeals to those of us who like our physics in discrete, countable bits. In the lattice formulation, quarks and gluons exist only at the nodes of a four-dimensional spacetime grid. There’s no evidence that the universe really has such a rectilinear structure, but it turns out to be a useful fiction when you want to calculate things like the masses of quarks. In large measure we are all made of quarks, and so it seems like a good idea to know some basic facts about them.

In my quest to figure out what lattice QCD is all about, I’ve had a lot of help. Years ago, as an editor of magazine articles, I had the splendid opportunity to get one-on-one tutorials from Kenneth G. Wilson and from Claudio Rebbi. I received further help for this latest project, and for that I want to thank G. Peter Lepage of Cornell.

In a paper titled “Lattice QCD for Novices” (written and published in 1998 but posted on the arXiv in 2005), Lepage presented a simple Python program that illustrates some of the key ideas behind lattice QCD. The complete source code for the program is given within Lepage’s article, but to save readers the trouble of gathering the pieces and extracting them from a PDF, I have (with Lepage’s permission) made the program available here in the file qcd.py. I’ve also made some trivial changes for the sake of compatibility with more recent versions of Python.

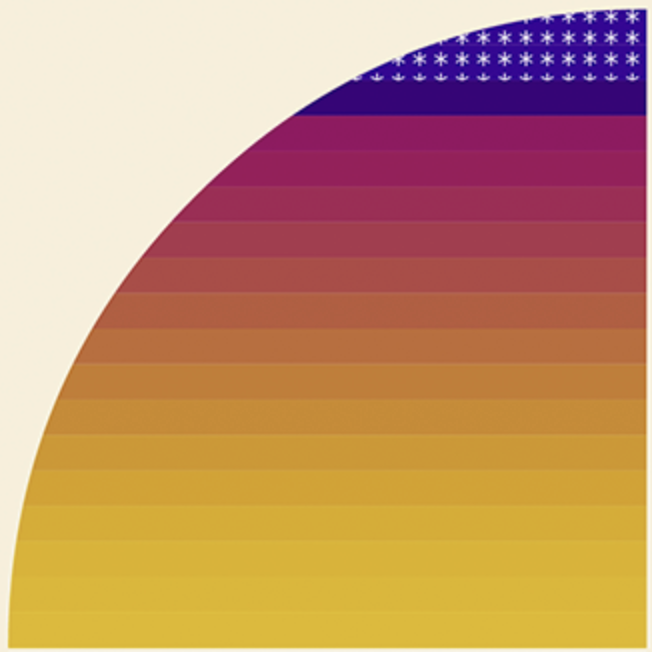

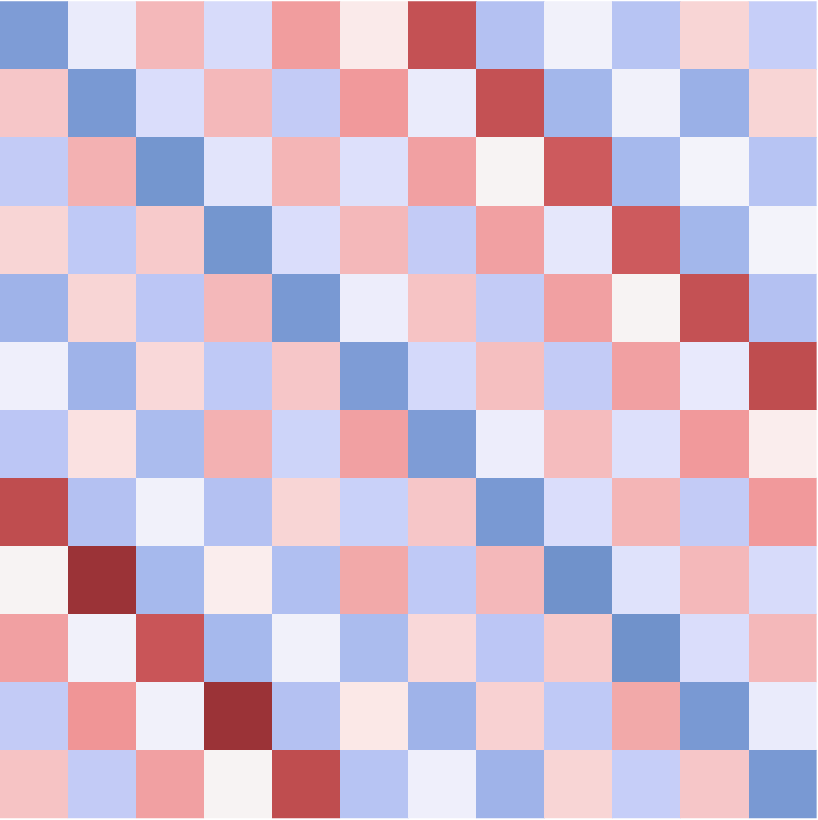

Finally, thanks too to Massimo Di Pierro of Depaul University for a vizualization of lattice QCD in action.

Publication history

First publication: 19 October 2008

Converted to Eleventy framework: 22 April 2025