Every spring it’s the same story. Those pendulous clusters of pinkish purplish blossoms come droopling off a pergola in a little park around the corner, and I spend the next half hour desperately searching my memory for the word. I know it’s in there, if only because I’ve been through this before, last year and the year before and the year before that. It’s in there but it’s stuck in one of the crevices of my cerebral cortex, and I can’t pry it loose. What is the name of that flower?

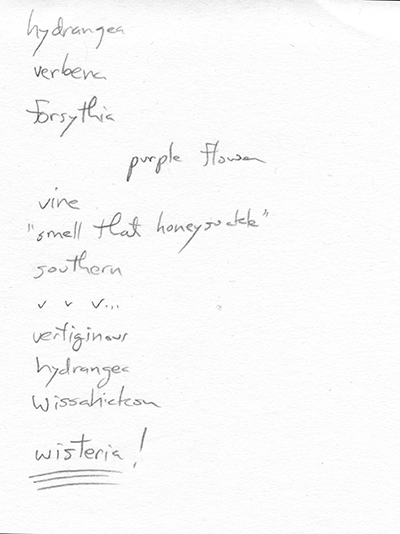

This year I took notes—looking over my own shoulder as I ransacked my mind for the missing word. The first term that came to me was hydrangea: obviously wrong but at least hitting the right general category of flowering plants. Verbena is a little closer—the flowers  of verbena are approximately the right color—but the strange thing is, I didn’t know that (or I didn’t know that I knew that) until I googled it just now. I do know what forsythia looks like, and I know it has almost nothing in common with the plant I’m trying to name, but my brain offers it up anyway.

of verbena are approximately the right color—but the strange thing is, I didn’t know that (or I didn’t know that I knew that) until I googled it just now. I do know what forsythia looks like, and I know it has almost nothing in common with the plant I’m trying to name, but my brain offers it up anyway.

The next entry in the list, purple flower, reveals the futility of trying to force the issue. That’s not my brain talking to me; that’s me talking to my brain, ordering it to give me the word I want. Vine may be in the same category, although the initial v could be significant (see below).

There’s a whole campfire story behind the next entry. Three boy scouts, their troop leader and two weeks’ worth of camping gear are crammed into a Volkswagen Beetle, circa 1962. As we putter down a back-country road, the scoutmaster leans his head out the window, inhales with exaggerated gusto, and exclaims, “Smell that honeysuckle!” All through the summer camp session we mocked him mercilessly for this excess of enthusiasm, but he has had his revenge: The phrase is tattooed on my left temporal lobe. It shows up every year when I’m entangled in this crazy quest to name the flower that’s not a hydrangea, not a verbena, not a forsythia, and not a honeysuckle either.

Southern: Me getting bossy with my brain again. When I lived in the Carolinas, I had a tree out front that was overgrown by the purple-flowered vine I can’t name.

v, v, v… Suddenly I’m sure the word starts with v, and this is the first moment when I feel like I’m making progress, that I have the scent, I’m on the trail. A v on the tip of my tongue, but not verbena, not vine…

Not vertiginous either.

And hydrangea—what are you doing here again? I already told you to go home; you’re not wanted.

Wissahickon Creek runs along the northwest boundary of the city of Philadelphia, toward Germantown and Chestnut Hill. There was a period in my youth when the road that winds along the creek was the route I took to visit a girlfriend. Late one rainy night I drove my 59 Chevy through deep water covering the road and soon had a white-knuckle moment when I discovered I had no brakes. It’s not surprising that I would remember all this, but what could it have to do with my unnamed flower?

And then, all of a sudden, the neuron finally fires. Wissahickon is not about the creek or the road or the girlfriend or the wet brakes; it’s all about the word itself. Not v but w… wis, wis, wis… I’ve got it now: wisteria! What a relief. (Until next spring.)

What is it about this genus Wisteria that so troubles my mind? There are scads of other plants I can’t identify, but that’s because I truly don’t know their names; no amount of rummaging in the attic of memory will ever succeed in retrieving what I never possessed. On the other hand, there’s a whole garden full of flowers—hydrangea, verbena, forsythia—that come effortlessly to mind, even when they are not wanted. Wisteria is different: something I own but can’t command.

Freud would doubtless opine that I must have suppressed the memory for some dark reason. I can play at that game. Wisteria is supposedly named for Caspar Wistar, notable Philadelphia physician circa 1800. He was inspired to study medicine after tending the wounded at the Battle of Germantown in 1777—an event that took place within cannon range of Wissahickon Creek. (Surely that can’t be a coincidence!) Dr. Wistar is also commemorated in the Wistar Institute of Anatomy and Biology in Philadelphia, a place I used to visit when I was a boy of 12 or 13. In that benighted age, impressionable children were allowed to wander freely through the Wistar’s collection of anatomical specimens, where various pickled body parts were sealed in gallon jars. What formaldehyde-soaked vision of horror am I trying so hard not to remember?

The trouble with this story is that until a few days ago I knew nothing of the connection between wisteria and Wistar. Not that Dr. Freud would let me off the hook for such a flimsy reason as that.

Of course wisteria is not the only word that my mind seems to be censoring. There’s that actress whose name I can never remember, although I have no trouble recalling that she’s the sister of Warren Beatty. And, along the same lines, the actor I can’t name, even though I can tell you he is the brother of James Arness. Can I find a childhood trauma to account for this distinctive histrionic sibling suppression complex?

Francis Crick wrote of our attempts to understand the brain: “We are deceived at every level by our introspection.” I believe it. I don’t think that looking over my own shoulder and taking notes as I free associate on the theme of pendulous purple flowers is going to resolve the mystery of memory. I’m fascinated by the process all the same.

In my latest American Scientist column I write on some other approaches to the question of what’s in Brian’s brain.