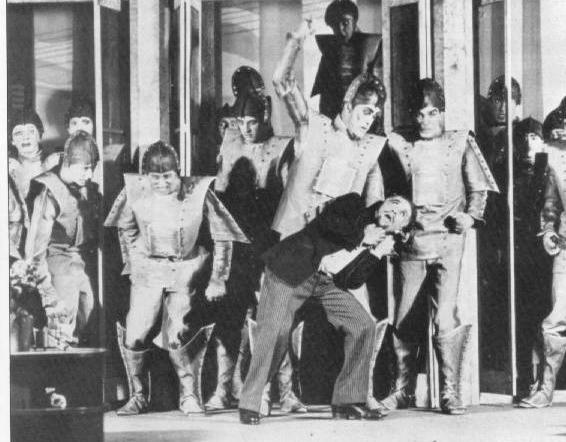

Murder by Robot in R.U.R. (Image from Wikipedia.)

Murder by Robot in R.U.R. (Image from Wikipedia.)

A number of thoughtful people (including Stephen Hawking, Nick Bostrom, Bill Gates) believe we should take the threat of AI insurrection seriously. They argue that in decades to come we could very well create some sort of conscious entity that might decide the planet would be a nicer place without us.

In the meantime there are lesser but more urgent threats—machines that would not exterminate our species but might make our lives a lot less fun. An open letter released earlier this week, at the International Joint Conference on AI, calls for an international ban on autonomous weapon systems.

Autonomous weapons select and engage targets without human intervention. They might include, for example, armed quadcopters that can search for and eliminate people meeting certain pre-defined criteria, but do not include cruise missiles or remotely piloted drones for which humans make all targeting decisions. Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology has reached a point where the deployment of such systems is — practically if not legally — feasible within years, not decades, and the stakes are high: autonomous weapons have been described as the third revolution in warfare, after gunpowder and nuclear arms.

When I last checked, the letter had 2,414 signers who identify themselves as AI/robotics researchers, and 14,078 other endorsers. I’ve added my name to the latter list.

A United Nations declaration, or even a multilateral treaty, is not going to totally prevent the development and use of such weapons. The underlying technologies are too readily accessible. The self-driving car that can deliver the kids to soccer practice can also deliver a bomb. The chip inside a digital camera that recognizes a smiling face and automatically trips the shutter might also recognize a soldier and pull the trigger. As the open letter points out:

Unlike nuclear weapons, they require no costly or hard-to-obtain raw materials, so they will become ubiquitous and cheap for all significant military powers to mass-produce. It will only be a matter of time until they appear on the black market and in the hands of terrorists, dictators wishing to better control their populace, warlords wishing to perpetrate ethnic cleansing, etc.

What would Isaac Asimov say about all this?

I was lucky enough to meet Asimov, though only once, and late in his life. He was in a hospital bed, recovering from heart surgery. He handed me his business card:

ISAAC ASIMOV

Natural Resource

No false modesty in this guy. But despite this braggadocio, he could equally well have handed out cards reading:

ISAAC ASIMOV

Gentle Soul

Asimov was a Humanist with a capital H, and he endowed the robots in his stories with humanistic ethics. They were the very opposite of killer machines. Their platinum-iridium positronic brains were hard-wired with rules that forbade harming people, and they would intervene to prevent people from harming people. Several of the stories describe robots struggling with moral dilemmas as they try to reconcile conflicts in the Three Laws of Robotics.

Asimov wanted to believe that when technology finally caught up with science fiction, all sentient robots and other artificial minds would be equipped with some version of his three laws. The trouble is, we seem to be stuck at a dangerous intermediate point along the path to such sentient beings. We know how to build machines capable of performing autonomous actions—perhaps including lethal actions—but we don’t yet know how to build machines capable of assuming moral responsibility for their actions. We can teach a robot to shoot, but not to understand what it means to kill.

Ever since the 1950s, much work on artificial intelligence and robotics has been funded by military agencies. The early money came from the Office of Naval Research (ONR) and from ARPA, which is now DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Military support continues today; witness the recently concluded DARPA Robotics Challenge. As far as I know, none of the projects currently under way in the U.S. aims to produce a “weaponized robot.” On the other hand, as far as I know, that goal has never been renounced either.