South wall. Hover to magnify.

A place where thousands of people suffered and died makes an uncomfortable tourist destination, yet looking away from the horror seems even worse than staring. And so, when Ros and I were driving from Prague to Dresden last month, we took a slight detour to visit Terezín, the Czech site that was the Theresienstadt concentration camp from late 1941 to mid 1945. We expected to be disturbed, but we stumbled onto something that was disturbing in an unexpected way.

Terezín was not built as a Nazi concentration camp. It began as a fortress, erected in the 1790s to defend the Austrian empire from Prussian threats. Earthen ramparts and bastions surround buildings that were originally the barracks and stables for a garrison of a few thousand troops. By the 20th century the fortress no longer served any military purpose. The troops withdrew, civilians moved in, and the place became a town with a population of about 7,000.

In 1941 the Gestapo and the SS siezed Terezín, expelled the Czech residents, and began the “resettlement” of Jews deported from Prague and elsewhere. In the next three years 150,000 prisoners passed through the camp. All but 18,000 perished before the end of the war.

Now Terezín is again a Czech town, as well as a museum and memorial to the holocaust victims. It seems a lonely place. A few boys kick a ball around on the old parade ground, the café has two or three customers, someone is holding a rummage sale—but the town’s population and economy have not recovered. The museum occupies parts of a dozen buildings, but many of the others appear to be vacant.

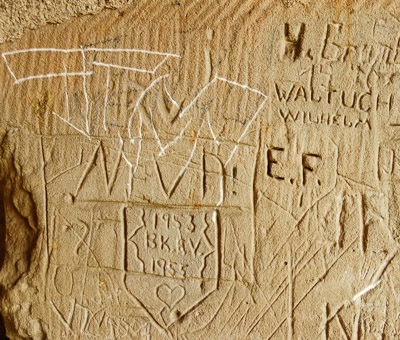

We looked at the museum exhibits, then wandered off the route of the self-guided tour. At the edge of town, near a construction site, a tunnel passed under the fortifications. Walking through, we came out into a grassy strip of land between the inner and outer ramparts. When we turned back to the tunnel, we noticed graffiti on the walls of the portal.

At first I assumed it was recent adolescent scribbling, but on looking closer we began to see dates in the 1940s, carved into the sandstone blocks. Could it be true? Could these incised names and drawings really be messages from the concentration-camp era? If so, who left them for us? Did the prisoners have access to this tunnel, or was it an SS guard post?

North wall.

I was skeptical. Too good to be true, I thought. If the carvings were genuine, they would not have been left out here, exposed to the elements and unprotected against vandalism. They would be behind glass in one of the museum galleries. But if they were not genuine, what were they?

I took pictures. (The originals are on Flickr.)

Back home, some days later, my questions were answered. Googling for a few phrases I could read in the inscriptions turned up the website ghettospuren.de, which offers extensive documentation and interpretation (in Česky, Deutsch, and English). Briefly, the carvings are indeed authentic, as shown by photographs made in 1945 soon after the camp was liberated. The markings were made by members of the Ghettowache, the internal police force selected from the prison population. A dozen of the artists have been identified by name.

The website is the project of Uta Fischer, a city planner in Berlin, with the photographer Roland Wildberg and other German and Czech collaborators. They are working to preserve the carvings and several other artifacts discovered in Terezín in the past few years.

I offer a few notes and speculations on some of the inscriptions, drawing heavily on Fischer’s commentary and translations:

|

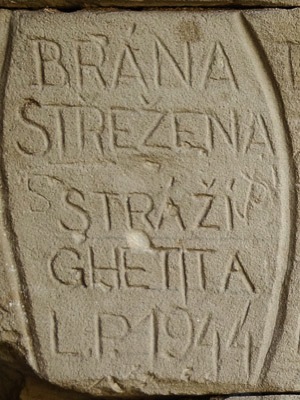

“Brána střežena stráží ghetta L.P. 1944.” Translation from ghettospuren.de: “The gate is being guarded by the ghetto guard, A.D. 1944.” This sign, given a prominent position at the entrance to the tunnel, reads like a territorial declaration. The date is interesting. Are we to infer that the gate was not guarded by the stráží ghetta before 1944? |

|

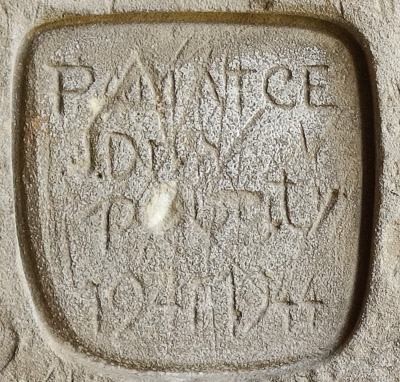

“Pamatce na pobyt 1941–1944.” Translation from ghettospuren.de: “In remembrance of the stay 1941–1944.” Fischer remarks on the formality of the inscription, suggesting that this part of the south wall was created as “a collective place of remembrance.” The carving has been badly damaged since the first photos were made in 1945. |

|

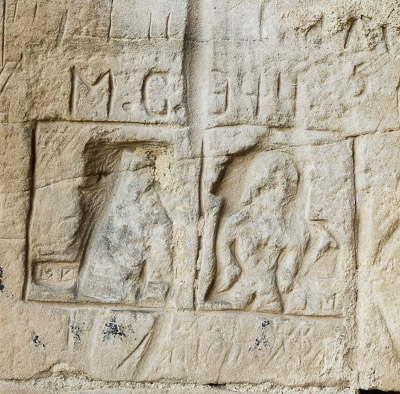

A floral arrangement is the most elaborate of all the carvings. Fischer identifies the artist as Karel Russ, a shopkeeper in the Bohemian town of Kyšperk (now Letohrad). Fischer writes: “In the top center there is still a recognizable outline of the Star of David that was already removed in a rough manner in 1945.” For what it’s worth, I’m not so sure that’s not another flower. The deep hole in the middle was not present in 1945 and is not explained. |

|

Four caricatures of the same figure are lined up on a single sandstone block on the north wall, with a fifth squeezed into a narrow spot on the block below. Why the repetition? And who was the subject? The Italian legend “Il capitano della guardia” and the double stripe on the hat suggest a high-ranking Ghettowache official. Did he take these cartoonish portrayals with good humor? Or could the drawings possibly be selfies? |

|

The menorah at the bottom left of this panel is the only explicitly Jewish iconography I have spotted in these images. (As noted above, Fischer believes the floral panel included a Star of David.) As far as I can tell, there are no Hebrew inscriptions. |

|

Portraits of a man and a woman? That’s my best guess, but the carving is indistinct. The line above presumably reads “M.C. 1944,” but the “1″ has been gouged away. |

|

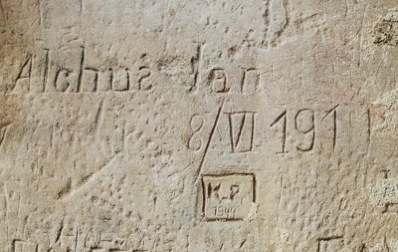

Not all of the inscriptions come from the Second World War. This one, signed “Alchuz Jan,” is dated |

|

It’s only to be expected that there are also later additions to the graffiti. Toward the bottom of this panel we have B.K. ♥ R.V. 1953. The white scrawl at top left is much more recent. On the other hand, the signature of “Waltuch Wilhelm” at upper right is from the war years. Fischer has identified him as the owner of a cinema in Vienna. Elsewhere he also signed his name in Cyrillic script. |

I am curious about the chronology of the Ghettowache inscriptions. Are we seeing an accumulation of work carried out over a period of years, or was all the carving done in a few weeks or months? The preponderance of items dated 1944 argues for the latter view. In particular, the inscription “In remembrance of the stay 1941–1944” could not have been written before 1944, and it suggests some foreknowledge that the stay would soon be over.

A lot was going on at Terezín in 1944. In June, the camp was cleaned up for a stage-managed, sham inspection by the Red Cross; to reduce overcrowding in preparation for this event, part of the population was deported to Auschwitz. Later that summer, the SS produced a propaganda film portraying Theresienstadt as a pleasant retreat and retirement village for Jewish families; the film wasn’t really titled “The Führer Gives a Village to the Jews,” but it might as well have been. As soon as the filming was done, thousands more of the residents were sent to the death camps, including most of those who had acted in the movie. In the fall, with the war going badly for Germany, the SS decided to close the camp and transport everyone to the East. Perhaps that is when some of the inscriptions with a tone of finality were carved—but I’m only guessing about this.

As it happens, the liquidation of the ghetto was never completed, and in the spring of 1945 the flow of prisoners was reversed. Trains brought survivors back from the extermination camps in Poland, which were about to be overrun by the Red Army. When Terezín was liberated by the Soviets in early May, there were several thousand inmates. But the tunnel has no inscriptions dated 1945.

Graffiti is a varied genre. It encompasses scatological scribbling in the toilet stall, romantic declarations carved on tree trunks, the existential yawps of spray-paint taggers, dissident political slogans on city walls, religious ranting, sports fanaticism, and much else. It’s often provocative, sometimes indecent, imflammatory, insulting, or funny. The tunnel carvings at Terezín evoke a quite different set of adjectives: poignant, elegiac, calm, tender. It’s not surprising that we see no overtly political or accusatory statements—no strident “Let my people go,” no outing of torturers or collaborators. After all, these messages were written under the noses of a Nazi administration that wielded absolute and arbitrary power of life and death. Even so—even considering the circumstances—there’s an extraordinary emotional restraint on exhibit here.

What audience were the tunnel elegists addressing? I have to believe it was us, an unknown posterity who might wander by in some unimaginable future.

When Ros and I wandered by, the fact that we had discovered the place by pure chance, as if it were a treasure newly unearthed, made the experience all the more moving. Seeing the stones in a museum exhibit—curated, annotated, preserved—would have had less impact. Nevertheless, that is unquestionably where they belong. Uta Fischer and her colleagues are working to make that happen. I hope they succeed in time.