Writing in The New York Times, the business columnist Eduardo Porter quotes Paul Ehrlich quoting Kenneth Boulding: “Anyone who believes exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.” Then Porter, siding with the economists if not the madmen, proclaims that economic growth must continue if “civilization as we know it” is to survive. (He doesn’t explicitly say the growth needs to be exponential.)

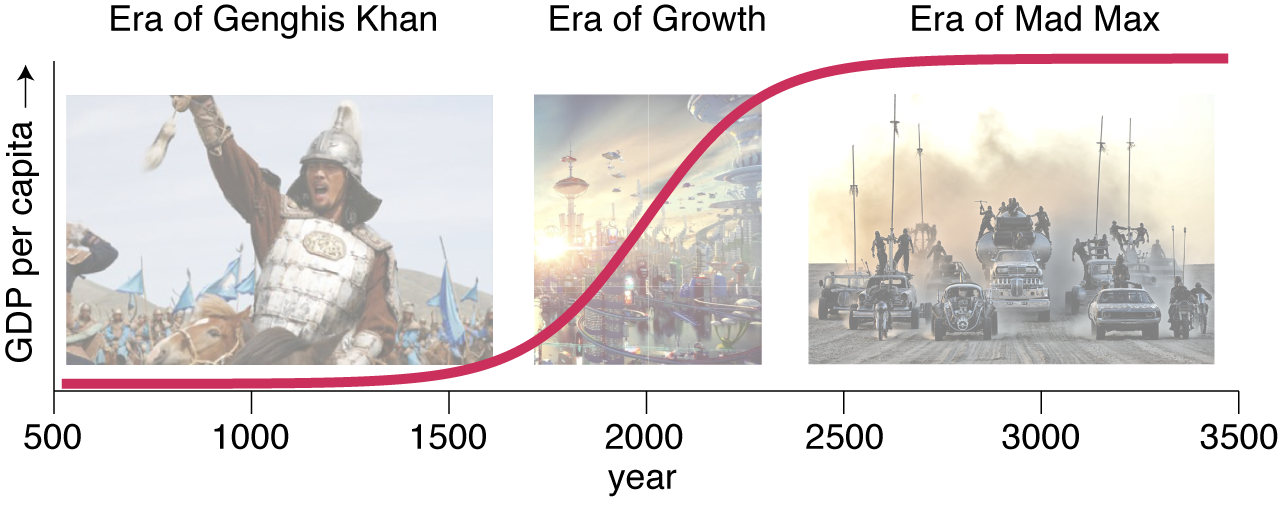

Porter links continuing growth not just to prosperity but also to a host of civic virtues. “Economic development was indispensable to end slavery,” he declares. “It was a critical precondition for the empowerment of women…. Indeed, democracy would not have survived without it.” As for what might happen to us without ongoing growth, he offers dystopian visions from history and Hollywood. Before the industrial revolution, “Zero growth gave us Genghis Khan and the Middle Ages, conquest and subjugation,” he says. A zero-growth future looks just as grim: “Imagine ‘Blade Runner,’ ‘Mad Max,’ and ‘The Hunger Games’ brought to real life.”

Let me draw you a picture of this vision of economic growth through the ages, as I understand it:

For hundreds or thousands of years before the modern era, average wealth and economic output were low, and they grew only very slowly. Life was solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. Today we have vigorous economic growth, and the world is full of wonders. Life is sweet, for now. If growth comes to an end, however, civilization collapses and we are at the mercy of new barbarian hordes (equipped with a different kind of horsepower).

Something about this scenario puzzles me. In that frightful Mad Max future, even though economic growth has tapered off, the society is in fact quite wealthy; according to the graph, per capita gross domestic product is twice what it is today. So why the descent into brutality and plunder?

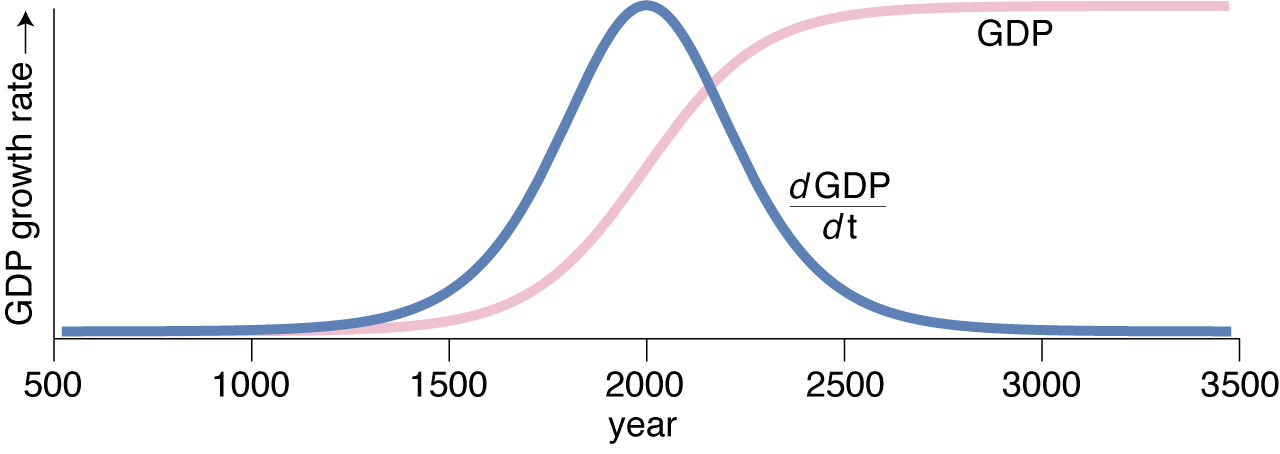

Porter has an answer at the ready. The appropriate measure of economic vitality, he implies, is not GDP itself but the rate of growth in GDP, or in other words the first derivative of GDP as a function of time:

If the world follows the trajectory of the blue curve, we have already reached our peak of wellbeing. It’s all downhill from here.

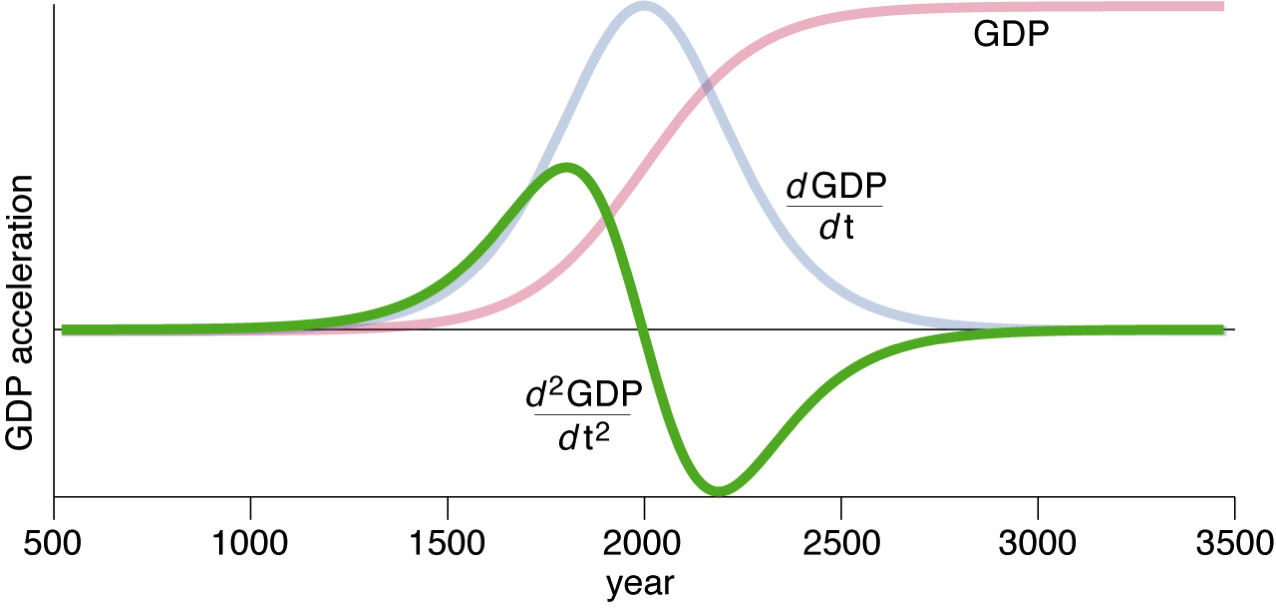

Some economists go even further, urging us to keep an eye on the second derivative of economic activity. Twenty-five years ago I was hired to edit the final report of an MIT commission on industrial productivity. Among the authors were two prominent economists, Robert Solow and Lester Thurow. I argued with them at some length about the following paragraph (they won):

In view of all the turmoil over the apparently declining stature of American industry, it may come as a surprise that the United States still leads the world in productivity. Averaged over the economy as a whole, for each unit of input the United States produces more output than any other nation. With this evidence of economic efficiency, is there any reason for concern? There are at least two reasons. First, American productivity is not growing as fast as it used to, and productivity in the United States is not growing as fast as it is elsewhere, most notably in Japan….

The phrase I have highlighted warns us that even though productivity is high and growing higher, we need to worry about the rate of change in the rate of growth:

Taking the second derivative (the green curve) as the metric of economic health, it appears we have already fallen back to the medieval baseline, and life is about to get even worse than it was at the time of the Mongol conquests; the Mad Max world will be an improvement over what lies in store in the near future.

Why should human happiness and the fate of civilization depend on the time derivative of GDP, rather than on GDP itself? Why do we need not just wealth, but more and more wealth, growing faster and faster? Again, Porter has an answer. Without growth, he says, economic life becomes a zero-sum game. “As Martin Wolf, the Financial Times commentator has noted, the option for everybody to become better off—where one person’s gain needn’t require another’s loss—was critical for the development and spread of the consensual politics that underpin democratic rule.” In other words, the function of economic growth is to blunt the force of envy in a world with highly skewed distributions of income and wealth. I’m not persuaded that growth per se is either necessary or sufficient to deal with this issue.

Porter’s essay on zero growth was prompted by the climate-change negotiations now under way in Paris. He worries (along with many others) that curtailing consumption of fossil fuels will lead to lower overall production and consumption of goods and services. That’s surely a genuine risk, but what’s the alternative? If burning more and more carbon is the only way we can keep our civilization afloat, then somebody had better send for Mad Max. The age of fossil fuels is going to end, sooner or later, if not because of the climatic effects then because the supply is finite.

Economic growth is not necessarily tied to the carbon budget, but it can’t be cut loose entirely from physical resources. Even the ethereal goods that are now so prominent in commerce—code and data—require some sort of material infrastructure. Ultimately, whether growth continues is not a question of social and economic policy or moral philosophy; it’s a matter of physics and mathematics. I’m with Kenneth Boulding. I don’t see Mad Max in our future, but I’m not counting on perpetual growth, either.