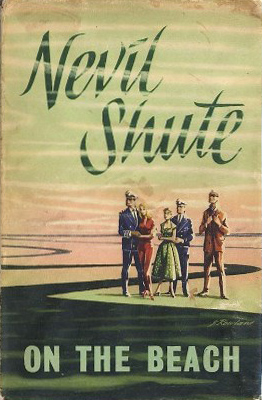

I’ve been rereading On the Beach, Nevil Shute’s novel about humanity’s last gasp in the aftermath of a nuclear war. The book was published 60 years ago, in 1957. I first read it in 1963, which is roughly when the events in the story are supposed to take place. It was also just a few months after the Cuban missile crisis, when annihilation was in the air.

I’ve been rereading On the Beach, Nevil Shute’s novel about humanity’s last gasp in the aftermath of a nuclear war. The book was published 60 years ago, in 1957. I first read it in 1963, which is roughly when the events in the story are supposed to take place. It was also just a few months after the Cuban missile crisis, when annihilation was in the air.

Spoiler alert: Everybody dies.

The setting is Melbourne, Australia, the southernmost major city on the planet. The entire population of the Northern Hemisphere was wiped out in the war, and airborne radioactivity is slowly creeping across the Equator. Darwin and Cairns, on Australia’s north coast, are already ghost towns, and the people of Melbourne are told they have less than a year to go.

A U.S. submarine takes refuge in Melbourne’s harbor. Over a period of weeks the captain of that vessel, Dwight, forms an attachment to a young woman named Moira. There’s affection on both sides, and maybe passion, but Dwight is determined to remain faithful to his wife and children back in Connecticut. He buys them presents: a diamond bracelet, a fishing rod, a pogo stick. He speaks of them in the present tense. Is Dwight delusional? Not exactly. He knows perfectly well that his family are all dead, and that he’ll never rejoin them except in the sense that he too will soon be dead. But those deaths are abtractions.

He had seen nothing of the destruction of the war . . . ; in thinking of his wife and of his home it was impossible for him to visualize them in any other circumstances than those in which he had left them. He had little imagination, and that formed a solid core for his contentment in Australia.

It’s not just Dwight who lacks imagination—or chooses to ignore the truths it reveals. Moira studies shorthand and typing for a future job that will never exist. Her father harrows fields for crops that will never grow. Another couple plant hundreds of daffodils whose blooms they will never see, and they invest in a lawn mower for grass they’ll never cut.

The author himself seems to share this selective connection to reality. Everyone in his doomed society is unfailingly polite, and usually cheerful. Civilization may be ending, but not civility. There’s not a single act of violence or malice or even selfishness in the entire story. Shute mentions no hoarding or profiteering, much less rape and pillage. No marauding bandits or desperate refugees from the contaminated north descend on this last haven. On the Beach is the antithesis of that other Australian vision of apocalypse: the Mad Max movies. (The first of the series, in 1979, was filmed near Melbourne.)

It’s also worth noting that no one in Shute’s world takes any steps to prolong life. The government is not hollowing out mountains to keep the human germ line going until the atmosphere clears. Families are not digging fallout shelters in the back yard. These last few representatives of Homo sapiens may indulge in a variety of follies, but hope isn’t one of them.

Why am I writing about this sad book just now? Well, obviously, it’s inauguration day. Which feels more like termination day.

The threat of nuclear disaster has continued to shadow us through all the years since Shute wrote his novel. The danger of a planet-scouring war seemed particularly urgent when I was 13 and reading On the Beach for the first time. I stood up in front of my eighth-grade English class to give an oral report on the book. My performance was not interrupted by a duck-and-cover drill, but it could have been.

Now we have handed control of 4,700 nuclear warheads to a petulant brat, and the danger seems greater than ever.

Revisiting that sense of menace is why I picked up the book, but it’s not what has made the strongest impression on me this second time around. I am both drawn to and appalled by the stoic acceptance of Shute’s fictional Melbournites. Given their circumstances, their reaction is not inappropriate. The worst has already happened, there’s nothing they can do to change it, they may as well make the best of it. In the face of certain extinction, what can you do but shrug your shoulders? Maybe the best way of muddling through is just to plant some daffodils.

Given the current mood of the nation and the world, I suddenly find it easier to understand Dwight’s behavior. The urge to pretend is powerful. I too want to believe that life can go on as normal, that I can continue to enjoy the private pleasures of family and friends, that I can retreat to a cozy office or library and lose myself in the world of ideas, in the “less fretful cosmos” of mathematics and science, or art and literature for that matter.

But we are not yet huddled on the beach, the last of the doomed. It’s late, but not yet too late. This is not the moment for resignation and acquiescence. Tomorrow we march!