There was a line at the Post Office window, so I went to the self-service counter, plopped my letter on the scale, and found that it weighed a whisker under two ounces. I bought stamps from the machine and stuck on a 39-cent and a 24-cent. I was just about to drop the letter in the slot when a thought struck me. I went back to the scale. Sure enough: With the stamps affixed, I was over the two-ounce limit.

I’m not going to tell you what I did next—whether or not I put an extra stamp on the envelope. That’s between me and my postmaster, and until they repeal the Fifth Amendment I have nothing more to say about it. But I will concede that my conscience may have been troubling me, because last night I dreamed of postal reform.

In my dream, the nation finally scraps the whole bizarre congeries of ad hoc step functions that currently define U.S. postage rates. Postage becomes a continuous function of a letter’s weight. (The current rate structure for domestic first-class mail appears to be a feeble attempt to approximate a simple linear function: P = 24W + 15, with the weight W in ounces and the postage P in cents.)

In the new regime we also dispense with the baffling collection of arbitrary stamp denominations. (Currently on sale at shop.usps.com: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 23, 24, 37, 39, 48, 60, 63, 70, 75, 83, 84, 87, 100, 385, 405, 500, 1440. (It’s not in the sequence server, and please don’t put it there.)) Sweeping away all this cruft, my dream Post Office sells postage in continuous strips and sheets with a defined value per unit area. You cut off a piece of the stuff—we can call it postage-tape, or maybe stampage—exactly as large as you need to pay the tariff on a letter of any given weight.

Better still, instead of measuring postage by the area of the stamp, we can measure it by the weight of the stampage stuff. The marvelous thing about this scheme is that the postage rate becomes a dimensionless quantity. Whether you express it in grams per gram or ounces per ounce, it comes out the same. The rate is a pure number. Let’s suppose it’s r = 1/10, just so we have something definite to talk about.

Now, when I take my letter to the Post Office, if it weighs, say, 50 grams, I know that I have to apply 5 grams of postage.

But wait. Now the letter-plus-stampage weighs 55 grams, and so the correct postage is 5.5 grams. When I add another half-gram of stamp stuff, the new weight is 55.5 grams, and the correct postage amount is 5.55 grams….

You may think that this endless series of adjustments to adjustments is a drawback of my new postal pricing model. Au contraire! It is the principal advantage. The benefits extend far beyond the Postal Service and promise to transform American life and culture, and especially education.

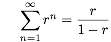

There is a scene that plays out every day in classrooms all across the country—or so I’m told. A high school kid, bored with a lesson on the summation of series, protests bitterly: “Why do I need to know this stuff? No way am I ever going to sum an infinite series in real life.” Now we have an answer for that young nihilist. Do you want to stand in the Post Office all day with cuticle scissors, cutting ever-smaller slivers of tape as you try to approximate the postage due on a letter? Or do you want to learn once and for all that

Here is America’s last best chance to be taken seriously as an educated and cultivated society. Nobody’s going to mess with a country where you need to know a little calculus just to mail a letter.

Addendum. Toward morning my dream took a darker turn. What if postal rates keep rising? Beyond, say, r = 1?