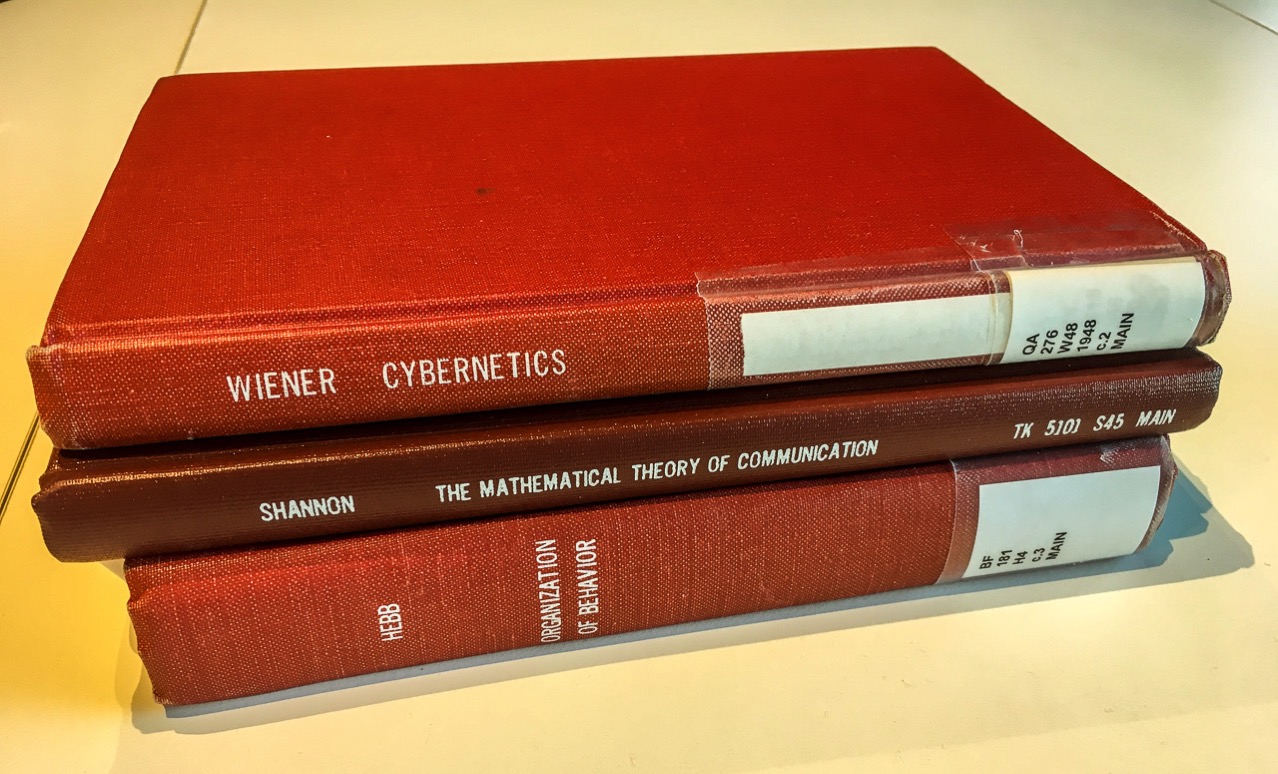

Three serious books lie open before me. I had a variety of reasons for checking them out of the library, although they’re all related in one way or another to current goings on here at the Simons Institute:

- Donald O. Hebb’s The Organization of Behavior: A Neuropsychological Theory. This is the book that introduced a fundamental hypothesis about learning and memory, captured in the slogan “Neurons that fire together get wired together.”

- Norbert Wiener’s Cybernetics: or, Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, an eccentric and wide-ranging masterpiece with a crucial chapter on “Computing Machines and the Nervous System.”

- Claude Shannon’s The Mathematical Theory of Communication, the foundational document of information theory. (Shannon’s part of this work had appeared a year earlier in the Bell System Technical Journal; the book version includes an interpretive essay by Warren Weaver.)

When I got the three volumes home, I made a surprising discovery: They were all published at roughly the same time, in 1948 and 1949. What are the odds of that? Perhaps it means nothing—just the long arm of coincidence reaching out to tap me on the shoulder. On the other hand, maybe there was something in the air circa 1950, something that made the period unusually fertile for studies of information, communication, and computation in brains and machines.

I have done a little digging in library catalogues and Wikipedia, as well as in my own files, looking for other titles that might belong on this list of distinguished midcentury milestones.

It turns out that George Kingsley Zipf’s Human Behavior and the Principle of Least Effort was also published in 1949. (This is the one about the curious power-law distribution seen in rankings of word frequencies, city sizes, and so on.)

Gilbert Ryle’s The Concept of Mind is another 1949 title, though I’ve never read it. Also from 1949: Nicholas Metropolis and Stanislaw Ulam published the first open account of the Monte Carlo method.

Drifting forward into 1950, we find another cluster of notables. There is John Nash’s one-page paper introducing what we now call the Nash equilibrium. Elsewhere in game theory, 1950 was the debut year for prisoner’s dilemma, although Merrill Flood’s paper describing it did not appear until two years later. Richard Hamming published “Error Detecting and Error Correcting Codes” in 1950. (It’s another paper from the Bell System Technical Journal.) Finally, there’s Alan M. Turing’s famous essay on “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.”

Does the density of high-octane publications really make 1948–50 an exceptional season of intellectual history? I can’t offer any solid statistical support for that notion. In the first place, my criteria for inclusion on the list are way too vague. (“Subjects I find interesting” may be closest to the truth.) In the second place, I can’t offer any evidence that other intervals were not equally productive. As a matter of fact, in my bibliographic rummaging I came across a nexus of brilliance five years earlier:

- Warren S. McCollough and Walter H. Pitts, “A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity,” 1943.

- John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern, Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, 1944.

- Erwin Schrödinger, What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell, 1944.

- Vannevar Bush, “As We May Think,” 1945.

- John von Neumann, “First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC,” 1945

I acknowledge a further reason for caution when I cite 1949 as a year of special distinction. It’s my year, the year of my birth.