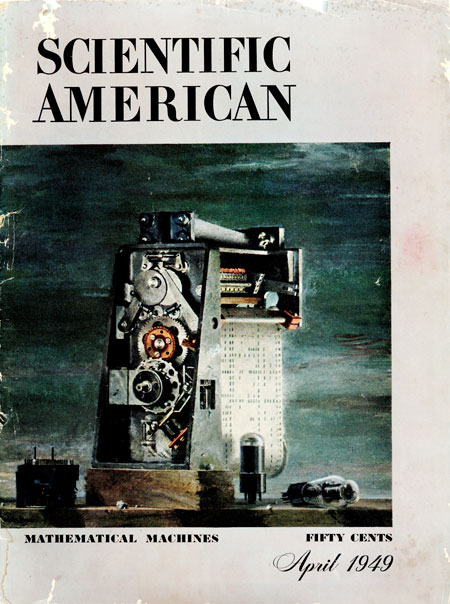

The tattered magazine shown above was on newsstands 60 years ago. You could have bought a copy for 50 cents—which wasn’t cheap at the time. The article featured on the cover, “Mathematical Machines,” surveys the whole topic of computational technology, from a primer on binary arithmetic to breathless reports on the hottest new machines—the Edvac, the Univac, Project Whirlwind. Other articles in the same issue include “Submarine Canyons,” “Greek Astronomy,” “Titanium: A New Metal” and “The Evolution of Sex.”

The creators of this ambitious magazine were Dennis Flanagan and Gerard Piel, two young writers who had become friends while working at Life magazine. In 1947 they set out on their own, planning to launch a wholly new magazine about science. When they learned that Scientific American was about to fold up after more than a century of publication, they bought it and made it over. By the time of that April 1949 issue, the new magazine had already found the formula and the format that would define it for a generation of readers.

One important part of the formula was a bit of an accident. Flanagan and Piel had expected to hire professional writers to produce the main articles, but they couldn’t find enough of them. So they began inviting scientists to tell their own story, in collaboration with an editor. This shortcut would soon become a key element of the magazine’s identity and its claim to credibility.

I grew up reading Scientific American, though I was not a subscriber. I discovered a disreputable shop on Race Street in Philadelphia that sold out-of-date issues for a dime each. These were copies with their covers torn off; years later I learned why. Newsstands are entitled to return unsold copies of magazines for full credit, but shipping all that paper back to the publisher was expensive and wasteful. So the dealers sent back only the covers and promised to pulp the rest of the magazine. Some of the discarded copies never made it to the recycling yard.

My adolescent reading of all those gray-market magazines was probably my main qualification when I joined the staff of Scientific American in 1973. I spent a decade there. I’ve done lots of other stuff since then, but the years with Flanagan and Piel were the great formative experience of my working life; in my own mind, I’ll always be a former editor of Scientific American. And I still have a deep affection for the magazine, even though I dislike what’s been done to it in recent years—so much so that I find it painful to read.

What went wrong? I think the genre of this story is tragedy: a noble enterprise undone by its own success. By the 1980s the magazine was prosperous enough to attract the attention of predatory investors. Their reasoning went something like this: If those eggheads can sell half a million copies and a hundred pages of ads with a magazine crammed full of physics and mathematics and molecular biology, just imagine how well we can do if we get rid of all that boring science. In 1986, under pressure from stockholders, the company was sold to Verlagsgruppe Georg von Holtzbrinck—by no means the worst of the suitors, but the terms of the purchase left the magazine desperate for new revenue. And the collateral damage was even sadder: Flanagan and Piel parted ways and never spoke again.

Over this past weekend I learned that Scientific American is going through another rough patch and will likely see further changes. (Sources: The New York Times, Folio, Portfolio.) Ad pages are down 18 percent. John Rennie, the editor since 1994, has “taken the opportunity… to find other engaging things to do.” At least 20 staff members will lose their jobs. The magazine will be uprooted from its own offices and will move in with the parent organization, Nature Publishing Group (another Holtzbrinck acquisition). Rumor has it that the new editorial direction will be even more consumer-oriented, focusing on science that’s “useful in everyday life.” The old commitment to articles “written by the scientists who did the work described” is under question.

I’ve been stewing over all this for a few days—or maybe it’s been a few decades. In any case, I’m tired of stewing; it’s time to move on.

At a personal level, I commiserate with those who are going to be hurt most—the staff members (including some old friends) whose jobs are in jeopardy. But in journalism and publishing these days we’re all sailing in leaky tubs and bailing as fast as we can.

When I take a step back and look at the larger cultural significance of these events, I think first of how important Scientific American was in my own upbringing and education. It’s my reflex to ask: How will kids like me get turned on to science without access to those coverless bootleg magazines at a dime a piece? But what a ridiculous question! The world has changed. The resources available today to a curious 14-year-old are far superior to anything I could have imagined back in the sixties. The little shop on Race Street was a treasure chest in its time, but it can’t compare with Wikipedia and the arXiv and PLoS and Weisstein’s World of Mathematics and Sloane’s Sequence Server and all the other bounty that’s now just a click away. Indeed, that’s a big part of the problem that faces Scientific American, and other publications.

We did good work at Scientific American, back in the old days. I’m proud to have been a part of it. But what we were building was not a monument to be preserved for the perpetual admiration of future generations. It was a channel of communication, a way of linking scientists with a broader audience. I believe it’s still important to keep those channels open, but the best way of doing it may be different in 2009 than it was in 1949.

On page 1 of the April 1949 issue of Scientific American is an advertisement from the Radio Corporation of America announcing—with considerable fanfare—the company’s latest innovation for audiophiles: the 45-rpm vinyl record. Today, the replacement of the replacement of the replacement of that recording medium is teetering on the edge of obsolescence. And yet music goes on! I want to believe that science journalism can also make a transition to a new medium, and perhaps come out of it better than ever.