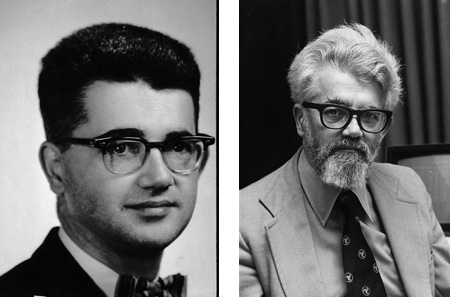

John McCarthy, the mind behind Lisp, died yesterday at age 84. The photographs below are from one of his web sites at Stanford. Many of his papers are available through a different web page. (I don’t know how long either of these sites will remain on the air.)

The Kiplingesque just-so story of how Lisp got its parentheses has been told several times, by McCarthy and others, but today seems an appropriate occasion to trot it out again. In the winter of 1958–59 McCarthy was at work on a paper that would eventually be published in Communications of the ACM as “Recursive Functions of Symbolic Expressions and Their Computation by Machine, Part I.” (There was never a Part II.) He was looking for good example programs to show that the new language was “neater than Turing machines” as a formalism for describing computable functions. In the end he came up with a demo much better than “Hello world!”

The following paragraphs are from McCarthy’s presentation to the first History of Programming Languages meeting in 1977 (ACM SIGPLAN Notices, Vol.13, No.8, August 1978; there’s an HTML-ized version).

Another way to show that LISP was neater than Turing machines was to write a universal LISP function and show that it is briefer and more comprehensible than the description of a universal Turing machine. This was the LISP function eval[e, a], which computes the value of a LISP expression e—the second argument a being a list of assignments of values to variables (a is needed to make the recursion work). Writing eval required inventing a notation representing LISP functions as LISP data, and such a notation was devised for the purposes of the paper with no thought that it would be used to express LISP programs in practice.

S. R. Russell noticed that eval could serve as an interpreter for LISP, promptly hand coded it, and we now had a programming language with an interpreter.

The “notation representing LISP functions as LISP data,” was the parenthesized prefix syntax now beloved by Lispers and reviled or ridiculed by just about everybody else. McCarthy himself was not a big fan of this notation. He believed—to the end of his life, as far as I know—that the language deserved a more conventional “algebraic” syntax, perhaps something in the Algol tradition. The parenthesized lists were called S-expressions; the elements of the fancier notation were to be called M-expressions. In the 1977 talk McCarthy continued:

The unexpected appearance of an interpreter tended to freeze the form of the language, and some of the decisions made rather lightheartedly for the “Recursive functions…” paper later proved unfortunate…. The project of defining M-expressions precisely and compiling them or at least translating them into S-expressions was neither finalized nor explicitly abandoned. It just receded into the indefinite future, and a new generation of programmers appeared who preferred internal notation to any FORTRAN-like or ALGOL-like notation that could be devised.

I guess I’m part of that new, unregenerate, generation, who have never been weaned away from their (((()))).

In 2005 I attended an International Lisp Conference at Stanford. McCarthy was present throughout the proceedings but kept a low profile until the final discussion session, when he rose from his seat to make this pronouncement:

If someone set off a bomb in this room, it would wipe out half of the worldwide Lisp community. That might not be a bad thing for Lisp, because it would have to be reinvented.

There were two provocative aspects to this statement. First, the lecture hall where we were gathered held no more than a couple of hundred people, so if we represented half of the of worldwide Lisp community, the whole outfit must be pretty small potatoes. Second, if obliterating half the Lisp community would be good for the language, then we must have gone badly astray somwhere in the past 50+ years.

My own view (for what it’s worth) is quite different. I’m simply amazed that so many fundamentally sound ideas were formulated so clearly so early in the history of computation. If McCarthy could get so much right in 1958, what the hell have we been doing since then?

• • •

One more reminiscence of John McCarthy. He was a great prognosticator and futurist. In the introduction to a Scientific American special issue on information (September 1966), he wrote presciently about a the prospect of putting a computer in every home and about what we now call cloud computing. (He filled in more details on these themes in a 1970 paper.)

No stretching of the demonstrated technology is required to envision computer consoles installed in every home and connected to public-utility computers through the telephone system. The console might consist of a typewriter keyboard and a television screen that can display text and pictures. Each subscriber will have his own private file space in the computer that he can consult and alter at any time.

But not all of McCarthy’s predictions were precisely on target. In 1989 he wrote about the threat of the fax machine:

Unless e-mail is freed from dependence on the networks, I predict it will be supplanted by the telefax for most uses in spite of the fact it is more advantageous…. Unless e-mail is separated from special networks, telefaxing will prevail because it works by using the existing telephone network directly.

I say we should let him slide on that one. Overall, the world is a richer place for his contributions to it.