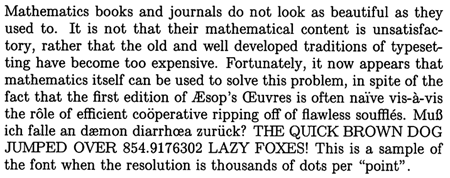

The curious document above was produced sometime in the spring of 1980 by Don Knuth to show off the typographical prowess of his new programs, TeX and Metafont. The software was then being introduced to the mathematical community through the publication of TeX and Metafont: New Directions in Typesetting, and I was writing a news item about it for Scientific American. At the time it seemed like a quaint, quirky and quixotic project, worth a column of type in the magazine even if nothing came of it in the long run. I would not have guessed that 30 years later TeX would be the foundation of a huge software superstructure—and would still be a part of my own professional life.

TeX is not the oldest software still in widespread use, but it may be the most stable. In the core of the system—the typesetting engine—very little has changed since 1990. And there will be even fewer revisions going forward. The current version of TeX is 3.1415926. Knuth has decreed that on his death the version number should be set equal to π and no further changes should ever be made. “From that moment on, all ‘bugs’ will be permanent ‘features.’”

I think—though this is subject to interpretation—that what Knuth wants to protect from all future meddling is not the text of the program itself, or even the underlying algorithms and data structures, but rather its operational specification. His intent in freezing TeX is to ensure that the same input should always yield the same output. Specifically, any software that calls itself TeX is supposed to pass his TRIP test suite.

I am of two minds about this policy. Mind One agrees with Knuth’s declaration: “Let us regard these systems as fixed points, which should give the same results 100 years from now that they produce today.” It’s comforting to think that all the TeX documents I’ve written over the years will still be readable a century hence. But Mind Two reminds me that in practice I have trouble maintaining TeX documents even for a few months, much less decades or centuries. What about those presentations done with the foils class that stopped working after an upgrade and that I’ve never bothered to fix? Or the articles using the pstricks package that won’t compile under pdflatex? TeX itself may be a fixed point in the software universe, but everything else spins dizzily around it.

The skeptical Mind Two has another argument as well: Under Knuth’s edict it’s not just the TeX markup language that can’t change; it’s also the architecture of the system. Knuth created his flawless soufflés and dæmon diarrhœa at an ASCII terminal wired to a PDP-10, and the only way he could see the product of his labors was to walk down the hall and retrieve hard copy from the AlphaType machine. We are no longer accustomed to such barbarities. TeX has been hauled halfway into the world of modern computing. Front-end software such as TeXShop provides a pleasanter interface. But the core programs still run in batch mode, as they did in the Dark Ages. To make even the smallest change in a document, you still need to throw away all the existing output and run a whole file (or set of files) through the compiler tool chain. Sometimes you have to do it twice. Or four times. Isn’t this ridiculous in a world of event-driven, interactive, multithreaded software? Will we still have to press the Typeset button in 2111?

Mind One replies: Of course not. By then we’ll just throw Moore’s Law at it: Automatically rerun TeX n times for every keystroke in the editor.

At this point Mind Three pipes up. (Did I mention that I’m of three minds?) The problem here, she says, is not that we can’t or shouldn’t alter TeX. It’s the utterly depressing notion that we’re incapable of building anything better, and that TeX will still be the typesetter to beat after another century. Surely, if we just stand tippytoe on the shoulders of Don Knuth, we can see a little farther. Who was the architect who said that every great building should have a bomb in the basement, set to blow itself up after 50 years and thereby clear the land for something greater still? Let’s make a new improved TeX. We’ll call it TNT.

Minds One and Two pounce in unison: You think we haven’t thought of that? What about ε-TeX? NTS? ExTeX? What about LuaTeX…?

• • •

This trinitarian meditation was inspired by a blog post I stumbled upon last week, in which an entity named Valletta Ventures, publisher of TeXPad for the Macintosh, attempts to port TeX (and also LaTeX) to the iPad; in this venture, Valletta Ventures eventually concedes defeat. The failure could be blamed on the scrutineers at the Apple App Store, who insist that every iPad program must be bundled up in a single executable. (My current TeX /bin directory has 342 entries.) But even if we were to let Apple off the hook here, the project still seems truly quaint, quirky and quixotic. Mind One says you shouldn’t expect to run a system as large and complex as TeX on a puffed-up cellphone. But Mind Two says: Why not? The iPad probably has more computational oomph than Knuth’s 1980 PDP-10.

In the end my sympathies lie with Mind Three, who sees the barrier to putting TeX on the iPad not as a lost opportunity but as a thin, bright glimmer of hope on the horizon. Maybe this protected market—the walled garden of Cupertino—will induce some young genius to create the next great mathematical writing system, an iPad app so good it will induce envy in all of us poor TeX users.

Looking at the issue more broadly, I think we often value stability and reliability a little too highly, and innovation too lowly. The world of computer science is overpopulated by walking fossils—not just TeX but also Unix, the Intel 86 architecture, TCP/IP. Quoting myself:

What has everybody been doing for the past 35 years? Can it be true that technologies conceived in the era of time-sharing, teletypes and nine-track tape are the very best that computer science has to offer in the 21st century?

As a remedy for this situation, the bomb in the basement may be a bit extreme. But I wonder if we shouldn’t try something like a reverse patent, where the whole world gets free use of an invention for the first 17 years, but then there’s an escalating schedule of royalties or taxes for those who fail to come up with a brighter idea.

• • •

One final question. When Knuth counts LAZY FOXES in his typographic specimen, where does he get the peculiar number 854.9176302? I would have thought 85491.76320.