It Was Twenty Years Ago Today...

by Brian Hayes

Published 9 January 2026

Happy birthday, bit-player.org. This site first entered the innertubes on 9 January 2006. Last summer I published a little essay that spoke about how it all began. I would like to mark today’s 20th anniversary by saying a few words about the World Wide Web, the marvelous substrate on which bit-player is built.

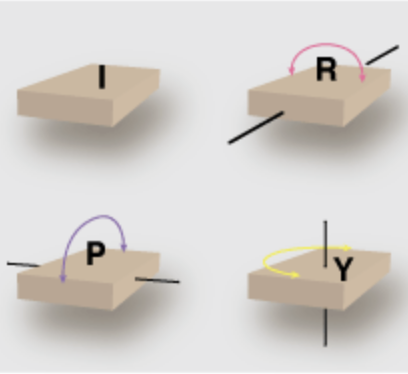

As a writer whose main subject matter is mathematics and computation, I find it hard to imagine a medium better adapted to my needs than the World Wide Web. The web itself is a computational artifact—a vast collection of computers talking to one another through a global network. I write and illustrate a story using my own computer, and at the far end of the line you view it with your own machine. I can send you words and pictures, as well as nicely formatted equations and source code. Via the web I can also do something that no ink-on-paper publication can promise: I can send you computer programs that will run on your machine, right there inside the web page.

Quite a lot of infrastructure is needed to keep the bits flowing through this network. There are racks of servers, miles of fiber-optic cable, plus routers and other switchgear all along the way. I pay a part of the cost of this equipment, through a monthly bill for the use of a server and its high-bandwidth connection. You pay too, in order to receive internet service at home or work. But the expense is orders of magnitude lower than the cost of printing and postage for a paper publication.

Also, web publishing is incredibly fast and friction-free. I push a button, you click a link, and these words appear on your screen seconds later. The system runs with remarkably little human intervention or supervision. I don’t have to seek anyone’s approval to publish on the web, and in most parts of the world you don’t need anyone’s permission to read what I’m saying. That this technology exists, and that it works, and that it’s widely available—this is one of the marvels of the modern age. But will it last?

I first became acquainted with the World Wide Web in 1993 on a visit to Fermilab, the particle-physics laboratory near Chicago. The computing group there showed me a tool they were using to read and write software documentation. The text scrolling across the screen was coming from the world’s first website, the one that Tim Berners-Lee had built at CERN, the European physics lab. Regrettably, that first exposure to the web didn’t make much of an impression on me. I didn’t even mention it in my article about computing at Fermilab, which appeared in American Scientist in January 1994.

Less than a year later, though, I was gushing about the wonders of the web in another American Scientist column. The web is transparent, I proclaimed: “Whether a node is in Geneva or New Zealand, it’s just a click away.” And the web is democratic: “It is a web, not a tree-like hierarchy. There is no official top node.” The web encourages sharing and discourages hoarding. I added an early warning about doomscrolling: “With the excuse of preparing to write this column, I have spent many late nights wandering the Web from one node to the next, glassy-eyed, weary, waiting to be entertained... Thus it appears we have another addictive, passive medium, ready to kidnap America’s children.”

Soon I was working to convert some of my own pieces for display on the web. The results were primitive. (See an example from 1995.) There was no hope of mimicking the geometric layout of a magazine page; I couldn’t even set the margins of a column of text. The only typographic niceties available were the HTML tags for italics and boldface. Indeed, the guiding philosophy in those early days was that content (or semantics) should be specified by the author but appearance should be left to the taste of the reader. (That didn’t last long.)

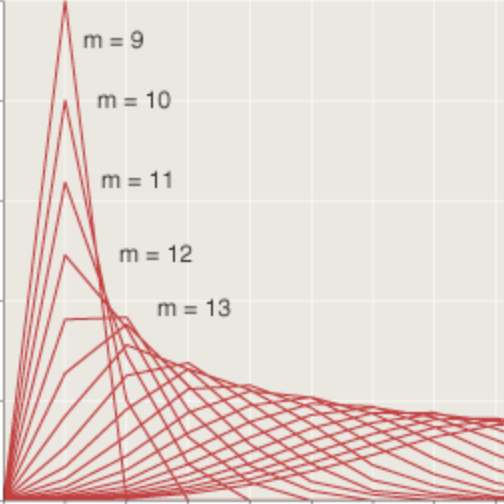

By the time bit-player went on the air in 2006, writing for the web was a reasonably pain-free process. HTML was still awkward and fussy, but we had a stylesheet language, CSS, for making things pretty, and JavaScript for making things move. Platforms such as WordPress and Drupal allowed non-wizards to run a website. Since then the tools for creating web content have grown even more powerful and sophisticated. Indeed, the abundance of choices can be overwhelming. (A public registry of JavaScript modules and libraries has more than three million packages.) I have never learned to use the fanciest and trendiest power tools, but I find the web a cozy and comfy place for writing both ordinary prose and computer code, especially for material that includes mathematical notation and elaborate graphics. When I want to show off computer simulations and the like, it’s the only game in town.

I feel lucky to have this splendid channel of communication available in my lifetime. It could not have existed any earlier than the late 20th century. I worry that it won’t last through the 21st.

Earlier attempts to bring computers and people together had a hub-and-spoke topology. A 1970 article by John McCarthy (pioneer of AI and fearless pundit on the place of technology in human life) imagined building such a system on a nationwide scale.

Visionaries have often proposed that homes be equipped with information terminals each consisting of a typewriter keyboard and a screen capable of displaying one or more pages of print and pictures. The terminal is to be connected by the telephone system to a time-shared computer which, in turn, has access to files containing all books, magazines, newspapers, catalogs, airline schedules, much additional public information not now kept, and various files personal to the user.

Through the terminal the user can get any information he wants, can buy and sell, could communicate with persons and institutions, and process information in other useful ways.

What McCarthy describes sounds something like the World Wide Web, with its ready access to everything ever published, but there’s a crucial difference. McCarthy puts all the documents in a central data repository. Web documents, in contrast, can reside anywhere in the world. And any computer with an internet protocol (IP) address can be a web server, offering up content to readers everywhere. (The servers could even include your car, your refrigerator, your doorbell.) I would not criticize McCarthy for failing to consider this alternative to the centralized system. He was writing before the first affordable personal computers hit the market, so the idea of a peer-to-peer network of millions of computers would have seemed ridiculous. Still, the distinction is important.

A centralized system implies centralized control. If I want access to McCarthy’s network, I can be asked to log in and prove my identity. If I misbehave, or if someone in authority distrusts me, I might well be locked out. With the distributed web, there’s no practical way to deny access. (Of course many sites on the web do require login credentials, but the web itself is open. There are technical means to block an IP number, but that number identifies the network node, not the human sitting at the keyboard.)

I consider it a major miracle that the web evolved in the way it did—as a distributed service with very little in the way of central authority or management. This was not entirely an accident; the designers of the first IP networks gave them that architecture deliberately, as a means of ensuring resilience. What’s amazing is that the net has (so far) withstood all attempts to subvert that anarchic design and impose some sort of central control.

Governmental meddling is one obvious threat to the autonomy of the web. Several countries, including China and Iran, closely monitor and often censor what their citizens can read and write on websites. In the U.S., there are complaints about both too much and too little regulation of internet speech. The Trump administration has mostly favored an anything-goes policy, but that could change at any moment. Even though there’s no easy way to lock out readers, government agencies certainly have the means to shut down publishers. You might question whether they have the legal right to do so. Good luck with that.

Governments aren’t the only powerful entities that might want to flex their muscles in this arena. In some ways the web is like the open range of the wild west in the 19th century; it’s a public good, a commons, available for all to use. The billionaires of Silicon Valley are the cattle barons who would like to fence off pieces of land for their own exclusive use. There was an attempt to do this in the 1990s, when America Online pitched their curated content as a superior alternative to the chaotic internet. On the strength of this prospect AOL became a darling of the stock market, bought the Time-Warner entertainment empire, and briefly became the fourth most valuable company in the U.S. Then they flamed out; at last report the remnants of AOL were being peddled to an Italian conglomerate called Bending Spoons. Thus do the mighty fall, but there are plenty of other services, from Facebook to TikTok to Truth Social, that strive to keep their users in a walled garden. The interests of those organizations seem to be at odds with the philosophy of an open web.

The risk that the web will be strangled by government or commercial interests is very real, but another sad fate may well be even more likely. Many fine ideas end not with a bang but a whimper. They merely fade away as some new fad comes into view. Am I saying the web is a mere fad? Surely this vital element of the world economy, a source of vast wealth, an inspiration to thousands of ambitious startup companies, a venue visited daily by billions of people searching for news and entertainment and commerce and gossip—such an institution is clearly too big to fail. Yes, I agree, it is. So was whale oil. Likewise the telegraph, the landline telephone, the Kodak camera, the video store, the backyard satellite dish, democracy. Let’s enjoy the web while it lasts.

Publication history

First publication: 9 January 2026