The Apex Generation

by Brian Hayes

Published 30 December 2025

Once upon a time, human generations carried names of poignant melancholy (the Silent Generation, the Lost Generation) or boisterous energy (the Baby Boomers). I don’t know who has bought the generational naming rights since then, but they have given us a string of dreary, bland monikers: Gen X, Gen Y, Gen Z. And now I hear we’re going to plod on into the Greek alphabet, with Gen Alpha and Beta. Generation Blah!

Here’s a counterproposal for naming the group of young people now in childhood and early adolescence. Let us call them the Apex Generation. According to projections from the United Nations, kids born within the past 15 years represent the last hurrah of a centuries-long spurt of population growth. They are the largest group of children the world has ever seen—and probably the largest it ever will see. In the U.N. projections, all subsequent cohorts are smaller. In other words, this is the world’s moment of peak childishness.

The news of this demographic turning point caught me by surprise, although I should have seen it coming. The human population is expected to top out at roughly 10 billion people sometime in the next 50 or 100 years, and then the numbers will begin a slow decline. If that’s to happen as a result of lower birth rates (rather than higher death rates), the retreat has to show up first among the youngest members of the species. After all, everyone begins life as a newborn.

The revelation that we have already entered the peak-child era comes from World Population Prospects 2024, the latest in a series of U.N. reports on demographic trends. The new edition analyzes historical population data from 1950 through 2023, and makes probabilistic projections up to the year 2100. Here’s the report’s vision of how the world’s total population will be evolving:

The black curve shows the historical record up to 2023. The solid red curve is the best-guess prediction of future behavior; it is the median of a few thousand probabilistic simulations with varying levels of fertility and mortality. Sixty of these simulated trajectories are shown as faint gray lines. The median trajectory peaks at about 10.3 billion people in the 2080s, then declines slightly in the final years of the century.

If we look only at the population of children, ages 0 through 14, the chronology is somewhat different:

In this case the peak in the curve is already behind us; it came in 2022. By the end of the century, according to the U.N.’s median estimate, the number of children under age 15 will have declined by about 17 percent, from more than 2 billion at the peak to fewer than 1.7 billion.

I should emphasize that these statistics and forecasts pertain to the global human population, and so migration doesn’t enter into the equation. (Not, at least, until Elonopolis starts welcoming Earthlings to Mars.) But that’s not to say the experience of these changes will be the same everywhere on the planet. If the U.N. predictions pan out, the most dramatic effects will be in China, which will lose more than half its population (dropping from 1.4 billion today to 639 million in 2100). The U.S., in contrast, is forecast to continue gaining population all through the current century (from 344 million now to 421 million in 2100). However, that forecast of ongoing growth is driven entirely by immigration. A zero-migration variant of the model shows the U.S. population dropping to 268 million. Given the policies of the current regime in Washington, that may be the likelier outcome.

Be Fruitful and Exponentiate

At first glance, the mechanism of growth or decline in the global population seems to be a simple matter of balance. If we have more births than deaths, then the head count grows; if deaths exceed births, the numbers shrink. How could it be otherwise? The rate of change is given by:

\[\frac{d N}{d t} = \beta N - \theta N ,\]where \(N\) is the global population, \(\beta\) is the birth rate per person and \(\theta\) is the corresponding death rate. The difference \(\beta - \theta\) is the net rate of increase or decrease, which we can designate \(r\). Assuming that \(r\) remains constant over time, this equation gives rise to exponential growth or decay. If \(N_0\) is the initial population, then at time \(t\) the population is:

\[ N_t = N_0 \, (1 + r)^t .\]For those who believe that every exponential must have an \(e\), we can rewrite the equation as \(N_t = N_0 \, e^{t \log (1 + r)}\). Each year’s gain or loss of population is proportional to the population itself during that year. It’s a more-the-merrier formulation: More people make more babies, although more lives also inevitably end with more deaths.

The one thing everybody knows about exponential growth is that it can’t go on forever. The demographer Ansley J. Coale vividly illustrated this point in a Scientific American article back in 1974. The world population then was about 4 billion, and the growth rate was 2 percent per year. If this rate were sustained, Coale wrote, “in less than 700 years there would be one person for every square foot on the surface of the earth; in less than 1,200 years the human population would outweigh the earth; in less than 6,000 years the mass of humanity would form a sphere expanding at the speed of light.” Do these numbers add up? I think the arithmetic is correct within an order of magnitude, although the physics of the third example is dubious. The population after 6,000 years would be \(10^{61}\), with a mass greater than that of the entire observable universe. We’d all collapse to form a human black hole.

Exponential growth is worrisome enough, but it turns out the observed law of human population increase is even scarier. Over the past two millennia we have been adding people at a superexponential pace. If you try to describe our proliferation with an expression of the form \(e^{kt}\), no fixed value of \(k\) yields an acceptable fit to the data. It seems \(k\) is not a constant but an increasing function of \(t\). As we grow, our rate of growth is also growing. Curiously, the superexponential law seems to be unique to the human species. Other biological processes, such as the reproduction of bacteria or cancer cells, make do with mere exponential growth.

What’s so scary about superexponentials? An ordinary exponential function zooms off toward infinity, but it gets to that destination only at the end of time, when \(t\) itself becomes infinite. A superexponential can reach infinity after a finite interval. In 1960 Heinz von Foerster, Patricia M. Mora, and Lawrence W. Amiot tried calculating the fate of humanity if superexponential growth were to continue. They concluded that we will burst all the bounds of mathematics and physics (to say nothing of biology) at \(t\) = 2026.87 ± 5.50 years. The title of their paper in Science dispensed with the error bars and announced: “Doomsday: Friday, 13 November, A.D. 2026.” So prepare yourself: We have less than a year before humanity explodes to fill the universe like a batch of overly rambunctious popcorn.

Booms and Echoes of Booms

The formulas given above express birth, death, and growth rates as fractions of the total population size. This is a common practice, and I’ll stick with it in most of the discussions below, but I must note that it ignores some important facts of life. Giving birth is a possibility only for a subgroup of humanity—specifically, those who ovulate. As for dying, any of us could do it at any moment, but G. Reaper is much more likely to visit people in my age bracket (75+) than those on the younger side of midlife. These factors suggest that a well-formed model of population dynamics ought to keep track of age and sex distributions.

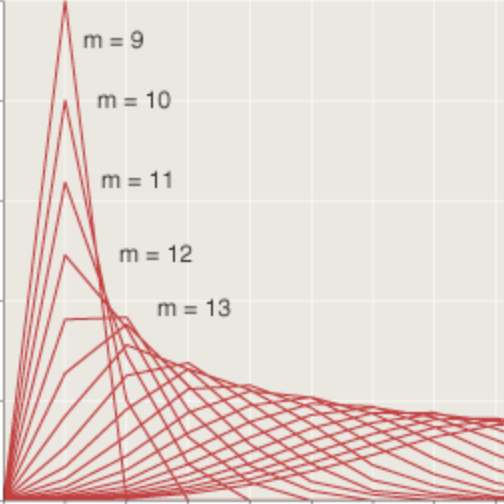

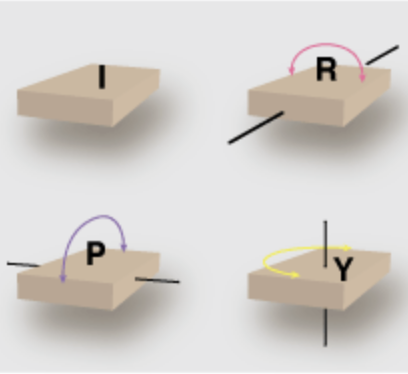

One device for vizualizing such distributions is the population pyramid, which consists of back-to-back histograms showing numbers of males and females in a series of age intervals. Some years ago I created an animated population pyramid based on the 2010 edition of World Population Prospects. For Figure 3 I have updated that code with the 2024 data. I have also updated the original program so that you can switch between the two data sets and compare their predictions.

In its initial configuration the pyramid shows the state of the world’s population in 1950, divvied up into two sexes (female pink, male blue) and 20 age groups spanning five years each. The controls at the upper right allow you to roam from the past into the future and back, again in five-year intervals. Looking at the 1950 graphic, you can see why it’s called a pyramid: It is widest at the bottom (the youngest cohort) and tapers to the top (the oldest). This shape is maintained throughout the sixties, seventies and eighties, as each subsequent cohort is larger than the one that came before, broadening the base of the pyramid. (Also, of course, the older cohorts shrink as they lose members through death.)

In the nineties something changes. The cohorts of 1990, 1995, and 2000 are all essentially the same size, so that the lower flanks of the pyramid are nearly vertical. Growth returns in the intervals beginning in 2005, 2010, and 2015, but then the trend reverses in 2020. After 2050 the shrinkage at the bottom of the pyramid accelerates—so much so that the shape is not a pyramid but an onion dome. No longer do young people make up the largest segment of the population; those under 25 are outnumbered by adults age 25 to 49.

Changes in age structure and gender balance can have a pronounced effect on overall population growth. For example, a baby boom creates a bulge in the population pyramid that travels upward through the age categories. When the members of that oversize cohort reach reproductive age, they create an echo of the boom—another boost in babymaking—even if the birth rate per person is unchanged. Parental biases that alter the gender ratio, such as a preference for sons over daughters, likewise have long-term consequences. A shortfall in female births now will reduce fertility 20 or 30 years later. The U.N. projections come from a population model that keeps track of age and gender structure.

The mention of baby booms brings to mind the surge of family building in the aftermath of World War II, lasting into the early 1960s. These events loom large in American memory (or at least in the memory of boomers like me), but they hardly register in the global statistics. In Figure 2 (the trace of population aged 0 to 14) the postwar boom and its echo in the 1980s appear as subtle changes in the slope of a curve that rises steeply for almost five decades. In contrast, the fluctuations of recent years show up as dramatic oscillations in the global curve. Growth in the youth population segment flattened entirely in the early 2000s, and in the 2020s it has reached a peak and begun a downturn. The U.N. projections show slowly dissipating waves continuing through the 2050s, but against a background of steady decline rather than growth. The change in momentum is quite recent. In 1990 the global average number of births per woman was 3.31; in 2024 it was 2.25. The average family has lost a child, and then some.

In Transition

Among demographers the leading explanation of these events is the notion of a demographic transition. The story goes like this: For many thousands of years, deaths of infants and children were commonplace, caused by famine or rampant infectious disease or other rigors and hazards of pre-modern life. Given those high death rates, a population could survive only by maintaining equally high birth rates. Our ancestors had to procreate like crazy, just to stay ahead of extinction. In the past few centuries, advances in agriculture, sanitation, and medical practice have greatly reduced childhood mortality, at least in the more prosperous and peaceable parts of the world. As death rates fell, high birth rates persisted for several generations, leading to rapid population growth. Eventually, though, a steep drop in the birth rate began to restore equilibrium. The population is stabilizing again, although at a higher level.

Figure 5 simulates a demographic transition for a hypothetical population that begins with 1 million people in 1800. For an interval of roughly 200 years births exceed deaths, causing the population to balloon more than fourfold. But once births and deaths are in balance again, there is no further increase.

The demographic transition is a concept I first encountered 50 years ago, when Scientific American published a single-topic issue titled The Human Population. At the time I was the new kid on the magazine’s editorial staff. In that role I had nothing to do with planning the issue, but I observed the process with keen interest.

Anxiety about overpopulation was at a peak in those years. Paul Ehrlich’s incendiary book The Population Bomb, published in 1968, warned: “In the 1970’s the world will undergo famines—hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death...” The Club of Rome’s report, The Limits to Growth, sounded the same note of dread, backing it up with the cachet of computer modeling. And Walt Kelly’s Pogo comic strip captured the mood of the moment, declaring “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

Anxiety about overpopulation was at a peak in those years. Paul Ehrlich’s incendiary book The Population Bomb, published in 1968, warned: “In the 1970’s the world will undergo famines—hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death...” The Club of Rome’s report, The Limits to Growth, sounded the same note of dread, backing it up with the cachet of computer modeling. And Walt Kelly’s Pogo comic strip captured the mood of the moment, declaring “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

Scientific American did not hop aboard the bandwagon of overpopulation panic; on the contrary, the tone of the issue was calm and optimistic. The 11 articles, all written by demographers or sociologists, argued that exponential growth would not continue long and would end without calamity. The world would be saved by the demographic transition.

My assignment for the issue was editing the Ansley Coale article mentioned above. Coale undertook to survey the entire history of human numbers. Of necessity it was a somewhat speculative story, since no one was counting noses until quite recent times. However, mere arithmetic reveals quite a lot about what was going on in those distant epochs. Assuming the species has been around for a million years, population growth during the first 990,000 years must have been glacially slow. Coale estimated that the average annual excess of births over deaths was 0.015 per thousand people. At that rate, if you survived to age 67, you might see your village of 1,000 people grow to 1,001 over the course of your lifetime.

But you probably didn’t survive to 67. Coale estimated that the average lifespan in the paleolithic was about 20 years. The average lifespan is not necessarily a typical lifespan. Suppose half the population dies in infancy and the other half lives to 40. No one dies at 20, yet that is the average age of death. From this number we can infer the average birth rate: It is the reciprocal of the average age at death, or in this case 1/20. That’s 50 births per year per 1,000 population—just enough to compensate for 50 deaths. This rigid linkage between life and death is a necessary property of any stationary population—one that’s neither growing nor shrinking.

The human population was very nearly stationary throughout most of it’s existence, and it is now thought to be evolving toward a new stationary state, which is expected to prevail into the distant future. If we accept the doctrine of a demographic transition, the recent era of rapid growth is an aberration, destined to be brief.

Why Now?

Back in 1974, the demographic transition made perfect sense to me. Now I’m not quite so sure I understand what’s happening. I don’t question the facts of the matter—the shift from high birth and death rates to low ones, with a period of excess births in between. But I’m not clear on what causes these changes in human behavior. How does it come about that billions of individuals, living in varied circumstances and cultures, all coordinate their choices in matters of family size? In particular, why are birth rates on the wane pretty much everywhere in the world? Is it a matter of choice—people have decided they just don’t want as many children? Or is the desire to reproduce being thwarted by external factors?

One summer I watched a pair of robins nesting outside my office window. They labored to build the nest, to defend it, and to brood the eggs. Then the real test began: The ceaseless demands of the squealing chicks kept both bedraggled parents foraging all day long. One worm after another. When the fledglings finally took off (without so much as a “Thanks, Mom”), I thought the empty nesters would seize the opportunity to kick back and pamper themselves for a while—visit the local bird bath, primp their plumage, hang out with the neighbors. Instead they immediately started over with a new clutch of eggs. I was both impressed and appalled by their dedication to the task.

To understand what motivated those frantic robins we don’t have to talk about instincts or desires, much less about love and duty. It’s enough to observe that if the population were made up entirely of individuals who can’t be bothered to breed, it wouldn’t have much of a future. A Darwinian imperative requires the birds to make as many babies as they can—or at least as many as they can raise to maturity. They must launch their genes into future generations. The same evolutionary mandate ought to apply to humanity as well, but as we come out on the far side of the demographic transition, we seem to be defying the rules—slacking off from maximum effort, producing fewer offspring than we could, failing to live up to our biological potential.

In Coale’s 1974 article, a figure caption offers to explain the falling birth rates. They are declining, it says, “primarily because of changes in the perceived value of having children.” Fifty years later, I read that sentence with a furrowed brow. As it happens, I wrote that caption. The words are my own. But I have no idea what I meant. Is the value of children subject to market fluctuations? What factors led to the devaluation? I should mention that I had a young child of my own at the time, whom my wife and I cherished. On the other hand, we had resolved to have no more children.

Economic themes turn up often in discussions of birth rates. The main argument goes like this: In a pre-industrial, agrarian society, children were assets, and so everybody wanted lots of them. You could put them to work in the fields or the dairy barn. Even in early industrial societies the young could earn their keep in the mills or the mines. Today, however, children have been moved to the other side of the ledger sheet; they are no longer a profit center but a major drain on the family budget. The estimated cost of raising a child from birth to age 18 is approaching $300,000 in the U.S. This number comes from Lending Tree. The U.S. Department of Agriculture used to estimate such costs, but the last publication came out in 2017, when their calculated expense was $233,610. At that price, children might be a luxury item beyond the means of many people.

A recent American Family Survey, conducted by Brigham Young University, supports this view. More than 70 percent of respondents felt that the cost of childrearing was unaffordable for most people. And 43 percent cited insufficient money as a factor limiting their own family size. The numbers suggest that people want more children but lack the resources to bring them up.

Other indicators, however, point in the opposite direction. Comparing the vital statistics of nations, it’s clear that higher income does not lead to higher fertility. On the contrary, the wealthiest countries are where birth rates began to fall first, and where they have fallen furthest. Within individual countries, the correlation between wealth and fertility is harder to sort out. If money is the issue, you might expect the very rich—those for whom million-dollar babies are a dime a dozen—to have larger families than the rest of us, and the poorest to be childless. I don’t think that’s true in general, but I don’t have the numbers to back it up. And even if the correlation is positive, causation remains unclear: Maybe it’s not that being rich allows you to indulge in having more children, but rather that having more children makes you less rich.

Another interpretation holds that prosperity itself is not the factor that suppresses national birth rates but rather a concomitant of increasing wealth. The richer countries, for the most part, offer women better access to education and career options other than marriage and motherhood. They marry later or not at all and thus have fewer children on average. The smaller family is a choice, not a sacrifice.

Here is yet another thesis: People have come to understand that further population growth will not make the world a better place, and so they choose to limit their family size for the common good of humanity, just as they choose to avoid gas-guzzling cars and plastic straws. I know that such people exist. I would love to think they are numerous enough to alter human destiny—that our fate will be determined by the force of moral convictions. But I don’t quite believe it. Although I am too much of a sentimentalist to accept that people plan their families by calculating the return on investment, I am too much of a cynic to swallow the idea that a significant number of couples forgo parenthood for the sake of the planet.

Perhaps I may be allowed to ask a silly question. Why do people want to have children in the first place? Because babies are so cute? Because we hope to relive our own childhood by proxy? Because we want to create a legacy—some trace of ourselves that will endure when we’re gone? Because it gives our lives a sense of purpose? The question really is silly—much like asking why we want to live rather than die—but, still, it ought to have an answer.

Steady On

On the far side of the great demographic transition lies a world where population is supposed to remain constant for the foreseeable future, neither exploding nor imploding. The 1974 Scientific American issue refers over and over to “stabilization” as the end point of the transition, although the authors never describe exactly what the term means in this context. Presumably, short-term fluctuations would be allowed, but the longer-term growth rate (averaged over a century, say) would be zero.

To keep the total number of persons steady, the birth rate and the death rate will have to be synchronized to quite high precision. During the recent era of rapid population growth, births exceeded deaths by only about 2 percent, yet the global population ballooned eightfold. Staying within 10 percent of a target number for a century or so would require that the two rates differ by no more than one part in a thousand—a major challenge, even if everyone on the planet were to agree that it’s the best policy.

Imagine you are a 22nd-century woman eager to do your part in maintaining a stationary population. How many children should you have? One simple rule says you should aim to replace yourself by having one daughter. If your first child is female, you should have no more. A consequence of this rule is that no girl child will ever have a sister. If your first children are all boys, continue until you have one girl, and then stop. If every woman follows this rule, and all their daughters do so as well, the number of childbearing women remains constant from one generation to the next.

The trouble is, not everyone can follow the rule, even if they want to. Some women will have no children. Some will have an unbroken series of males and arrive at menopause without a daughter. Some daughters will not survive to puberty. Because of these deficiencies, the one-daughter rule leads to a gradual but steady decline in the number of women (and a glut of males).

An alternative formulation defines a replacement-level birth rate as an average of 2.1 children per woman, regardless of gender. That this number is roughly 2 is easy to understand: One son and one daughter, on average. The number is slightly greater than 2 in part because not all daughters will survive to have children of their own. Another factor is that the natural sex ratio for human births favors males by about 1.05 to 1.

Unfortunately, specifying a birth rate for the average woman offers no clear guidance for the individual. Given that other women may have fewer than or more than 2.1 children, how many should you have if you want to maintain the correct average? Without comprehensive knowledge of the whole population, it’s impossible to say. Also, the fixed-birth-rate rule has no mechanism to cope with unexpected changes in circumstances. For example, if some major country were to elect a bunch of stooges who want to abolish vaccination for childhood diseases, the 2.1-child average would soon fall short of replacement level.

There’s one sure-fire way to achieve zero-population growth: Yoke together births and deaths. The idea is implicit in a song written by Laura Nyro back in the 1960s. She wrote (at age 17): “And when I die, and when I’m gone, there’ll be one child born in the world to carry on.” This simple rule guarantees that every death will be matched with a birth. We also need to enforce a linkage in the opposite direction. As Nyro might have added (but didn’t): “And on the night my child is born, there’ll be one geezer dyin’ before the morn.”

The Nyro recipe ensures that global population remains constant, and that birth and death rates are always equal, but that’s no guarantee of a stable, never-changing demographic status quo. There could still be large fluctuations in births and deaths—they just have to move in tandem—and the age structure could shift drastically. Suppose a sudden epidemic wipes out half the world’s senior citizens. Women of reproductive age would have to boost births to make up for the losses. Millions of old fogeys would be exchanged for an equal number of infants. And the disruption doesn’t end there. Twenty-some years later, the deficit of old people continues to reduce the death rate. At the same time there’s a surplus of young people just reaching the peak age for childbearing. They will have to curtail their reproductive activity lest the life-and-death balance be upset.

The Unique Moment

According to standard accounts of the demographic transition, the overall trajectory of the human population should look something like this:

From deep in the remote past up to the present moment, the graph of human numbers is nearly flat, with a growth slope so shallow it’s imperceptible. Then comes a singular event: an explosive spurt producing a huge bump in the curve. Once that excitement is behind us, the statistics of human life resume their boring, unvarying course far into the future. Growth is again near zero, although the absolute number of people is much higher.

Something about this picture bothers me. Cosmologists are fond of citing the Copernican principle, which says that if you look around and find yourself in a very special place, such as the center of the universe, you are surely wrong. Your senses are fooling you. A temporal version of the Copernican principle warns that if your lifetime seems to coincide with some unique event in the history of the world, this too is likely a delusion.

Figure 6 clearly gives the impression that we are living at an extraordinary, unprecedented, and never-to-be-repeated moment. Within my own lifetime, the world’s population has tripled. Has anything like this ever happened before? We can’t rule it out from the evidence of history and prehistory. We know the average rate of growth was very small, but there might well have been large fluctuations around that average. Furthermore, the average is calculated for the entire planet, but until recently the concept of a global population had little meaning. No one was keeping track of the worldwide head count—not at a time when whole continents were ignorant of each other’s existence. Regional populations, more or less isolated, might be growing or shrinking, but the changes are largely uncorrelated, and so they average out to zero. A bloom in southern Africa is balanced by a swoon in Europe.

The onset of the demographic transition has been attributed to industrialization, urbanization, education, prosperity, improvements in nutrition and public health, and new opportunities for women outside the home. Alongside all these factors I would call attention to another collateral effect of modernity: Previously isolated communities have coalesced into a global whole, with economic and cultural ties knitting together distant regions. Not that we have achieved the dream of One World, but networks of transport and communication are efficient enough that events near and far are no longer uncorrelated. When we go through cycles of boom and bust, they are likely all in synchrony. One vivid illustration of this effect concerns infectious disease. Viruses and other pathogens can spread worldwide in weeks rather than years; but the tools for fighting those diseases also travel faster. Of special note is the eradication of smallpox, which must be accomplished everywhere, or else no one is safe anywhere.

What about the future? According to Figure 6 we can expect another featureless, flatline population graph; once we complete the demographic transition, nothing of note will ever happen again. This was the prediction of the demographers writing for Scientific American back in 1974, though they offered no explanation for this ongoing stasis. The U.N. projections from 2024 do not show such a stabilization; by 2100 there’s a slight decline in overall numbers, and the steeper loss of young people suggests this trend will continue, at least for a generation or two.

It’s worth mentioning that sustained exponential decay is just as devastating as exponential growth. Losing 2 percent per year leads to extinction of the species in a little more than 1,000 years.

Beyond the Apex

After decades of hand-wringing over the terrors of overpopulation, it feels weird to hear people fretting about the threat of depopulation. Why does it make us uncomfortable to see the number of people dwindling, even when we know that reducing our footprint is in our own (and our children’s) best interest? In this connection one might ask: What is our moral obligation to future generations? At a minimum, you might well reply, we owe them existence. After all, they can’t get here without us. (Perhaps this is also an answer to my silly question about why we have children.)

Apart from any purported duty to perpetuate the species, there are also genuine, material challenges brought on by depopulation. In many cases the critical factor is not whether the population is larger or smaller but whether it’s growing or shrinking.

In the context of classical, Adam Smith–style economics, a growing population should be a boon to capitalists. It creates an ever-expanding market for goods and services, increasing demand and therefore pushing up prices. At the same time, the supply of labor also increases, holding down wages. Win-win for Daddy Warbucks. By the same logic, a falling population would seem to favor the wage-earner. As the number of workers decreases, those who remain can demand better pay, while a contracting market for consumer goods should lower prices. It’s not clear, however, that real economies follow these rules, particularly when a substantial share of resources is being siphoned off into products and services that only the ultrarich can afford.

Changes in the age structure of the population also have economic consequences. In a world with fewer children, we’ll be converting schools and playgrounds into retirement communities. When the diminished cohorts of children grow up and enter their working years, they will face the burden of supporting a superabundance of elders. Even more than today’s young people, they may not be able to afford having children, which will of course accelerate the downward trend in population. Here is the final piggish act of the boomer generation: We say to youth, “You can’t have kids; you need to save your pennies to support your aging parents and grandparents.”

For wealthy countries, an obvious way of ameliorating (or at least delaying) this crisis is to encourage immigration. The idea is to import young adults ready for work, so that you don’t have to pay for their upbringing or education; then you exclude them from social-welfare plans but not from taxation; when they are too old to go on working, you send them back where they came from. This sort of rapacious, exploitative policy is exactly what I would expect from the me-first government now ruling the U.S. Unaccountably, the Boomer in Chief is doing just the opposite.

Countries on the leading edge of the demographic transition are certainly anxious about the impending loss of population, but their preferred strategy is not immigration but “pro-natalism.” They want to encourage their own citizens to have more babies. So far the results are unimpressive. Hungary offers grants of $30,000 to couples who agree to have at least three children, as well as paid parental leave from work, and a lifetime income tax exemption for the mother. With these inducements the crude birth rate rose from 1.25 to 1.61 a few years ago, but that’s still far below the replacement level. And at last report the rate had dropped back to 1.39. In the U.S., the offer of a $1,000 “Trump account” for newborns seems like an awfully paltry incentive.

Looking beyond economic issues, I wonder how the experience of life will change in a world with fewer children. When my own Boomer generation swaggered onto the scene in the 1960s, we exulted in our numbers, and we vowed to remake the world in the image of youth. We were going to ban the bomb, give peace a chance, reconcile the races, abolish poverty, liberate women, save the planet, expand our consciousness. The tragic part is not that we failed. It’s that we grew up, and then grew old, and we didn’t have the good grace to believe our own slogan: Don’t trust anybody over thirty.

The Apex Generation is now on the threshold of adulthood. The cohorts to follow will not outnumber their elders, and they will not be able to outvote them, or outbreed them. They’ll have to outwit them. I’m cheering them on.

Further Reading

Aitken R. John. 2022. The changing tide of human fertility. Human Reproduction 37(4):629–638. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deac011

Ehrlich, Paul R. 1968. The Population Bomb. New York: Ballantine Books.

Foerster, Heinz von, Patricia M. Mora, and Lawrence W. Amiot. 1960. Doomsday: Friday, 13 November, A.D. 2026. Science (4 November 1960) 132:1291–1295.

Thompson, Warren S. 1929. Population. American Journal of Sociology 34(6):959–975.

Van Winkle, Zachary, and Christiaan Monden. 2022. Family size and parental wealth: The role of family transfers in Europe. European Journal of Population 38:401–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-022-09611-w

Publication history

First draft: 24 September 2025

First publication: 30 December 2025

Minor edits: 1 January 2026