IMG_1134

by Brian Hayes

Published 18 September 2012

Lots of digital cameras come with a default file-naming scheme of IMG_nnnn, where nnnn is a four-digit number assigned sequentially, starting with 0001. The four images above are photos I made with four different cameras over a span of more than a decade, but they all have the same filename: IMG_1134.JPG. As you might guess, name collisions cause occasional trouble when I decide to merge folders. I could easily fix the problem at the source—all of the cameras allow for an override of the default naming scheme—but I’ve never bothered. And I’m not the only one.

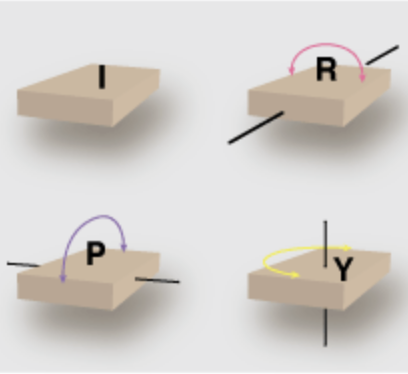

The other day it occurred to me that the prevalence of IMG_nnnn filenames offers a way to “randomly” select a sample of images from public archives such as Flickr. Here’s a collage of results produced by searching Google Images with the query string “IMG_1134″:

Below is a similar collage generated by running the same search query on Flickr:

And finally I offer a specimen of what Bing Images delivers for “IMG_1134″:

In what sense are these selections random? The rationale is this: If we choose the 1,134th picture taken with many cameras by many photographers, I wouldn’t expect much correlation in the subject matter of those images. And indeed the samples above do seem to cover a pretty wide range.

On the other hand, I wouldn’t try to argue that the method produces a totally unbiased sample. The most serious problem is that the list of images returned by a search engine is not itself randomized. Google and Bing rank images according to the estimated prominence of the web pages they appear on. Flickr offers three sorting orders—”relevant,” “recent” and “interesting”—but does not have a “random” option.

In the samples above I dealt with this issue in various ad hoc ways. For the Google Images sample I made the selections based on computer-generated pseudorandom numbers. In the case of Flickr I took every seventh image. On Bing I scrolled down past the first few thousand thumbnail images and then copied an arbitrary rectangular region of the screen. These are feeble attempts at randomization; no doubt the selections still favor higher-ranked or more popular images.

Another source of bias is that we’re only seeing images that people chose to save and to share. The pictures you take with your thumb on the lens are likely to be deleted; unflattering portraits of your spouse will not be uploaded.

Still another bias is subtler and more interesting: Not all nnnn‘s are the same. A camera that gets used for a few weeks when it’s fresh out of the box and then gathers dust in the closet over subsequent months and years will never reach the IMG_9000s, and maybe not even the IMG_1000s. To test this hypothesis I ran a search on Google Images for each string of the form “IMG_nn00,” from “IMG_0100″ through “IMG_9900.” For each search string I recorded the number of hits reported by Google:

Over much of the range, the number of images decays in a way that looks vaguely logarithmic—but then something weird happens at about nnnn = 6000. I suspect that the weirdness comes from a glitch in Google’s classification and counting algorithms rather than from the habits of the worldwide community of photographers. To test this idea I reran the same script on Flickr, with these results:

The scale is different but the shape of the distribution is very similar—without any spiky weirdness at the high end. A logarithmic curve fits quite well.

As the number of IMG_nnnn images falls off with increasing nnnn, the nature of the images may also change. In particular, one might suppose that photographers who practice their craft enough to make several thousand images would produce more accomplished and more interesting results. In other words, by looking at the higher-numbered images, we may weed out the dilettantes.

I grew curious about IMG_0001. What kinds of pictures do people take when they first unpack a new camera, charge up the battery, and begin clicking the shutter? I expected a lot of self-conscious and self-referential images like these:

Obviously I found a few, but I had to sift through several hundred Flickr IMG_0001 thumbnails to come up with these four. (There were also a few pictures of camera boxes and packaging.) To my surprise, the vast majority of IMG_0001 photos did not look at all like test images made with a new toy. Not unless people unpack and test their new cameras inside the Hagia Sophia or on the south rim of the Grand Canyon or at a basketball game.

So what’s going on with the 0001s? Perhaps through some metadata mixup, multiple images are all getting labeled “IMG_0001,” even though that’s not the filename coming out of the camera. But if that’s the case, “IMG_0001″ ought to be an outlier, with substantially more exemplars than neighboring file names IMG_0002, IMG_0003, etc. The data indicate otherwise:

An alternative explanation is that photographers frequently reset the camera’s file counter to 0001. Here’s still another possibility: Maybe some of those IMG_0001 pictures are not the camera’s first image but its 10,000th. I’ve never gone all the way around with a camera, so I don’t know exactly what happens when the counter turns over. Is IMG_9999 followed by IMG_0000? (I note that a Flickr search for “IMG_0000″ returns 2,430 results. It’s the tiny leftmost lollipop in the graph above.)

• • •

Even if searching for IMG_nnnn offers only a crude level of randomization, I think it may still hold some promise of showing us what average or typical photographs look like. How many are portraits and how many are landscapes? Taken indoors or out? What fraction of all photos show children? Pets? What are the proportions of men and women?

Based on a casual perusal of a few thousand photos, I was led to make some tentative observations:

- The genre of family snapshots—children’s birthday parties, vacation trips to Disney World—is not nearly as prominent in these collections as I would have expected. I guess those pictures are all on Facebook.

- Food, on the other hand, is a much more popular subject than I ever would have guessed. In a sample of 100 Bing images, 21 showed comestibles of some kind. Is it really true that a fifth of all the world’s pixels are being used to show what we ate for lunch?

- Vehicles are not quite as everpresent as meals, but there sure are a lot of cars, bikes, trains, trams and aircraft to be seen. It seems a lot of people want to show off their ride.

Addendum: Here’s the data behind the three graphs above.

Responses from readers:

Please note: The bit-player website is no longer equipped to accept and publish comments from readers, but the author is still eager to hear from you. Send comments, criticism, compliments, or corrections to brian@bit-player.org.

Publication history

First publication: 18 September 2012

Converted to Eleventy framework: 22 April 2025

Would you mind posting the data for the graphs? I’d like to use it in my math modeling and statistics classes, and I would guess that many other people would as well. Thanks!

@Andrew Ross: I’ve added a link to the data, although I wonder if your students wouldn’t have more fun wrangling it out of the web for themselves. In any case, if they learn anything interesting, I hope they will let us know!

When someone who’s already a practiced photographer buys a new camera, their IMG_0001 is likely to be quite different in subject matter from someone with their first digital camera.

It’s not really an indicator of a new camera to get IMG_0000 or IMG_0001 but rather a new or newly formatted *flash card*. perhaps people frequently go on vacation and get themselves a new bigger flash card to take lots of pics on, or similarly perhaps they tend to download everything off their flash card and then format it before going somewhere to take lots of pics.

Also, people who are competent photographers tend to buy themselves new cameras and flash cards frequently.

@Daniel Lakeland: I’ve just tested this with three cameras (a Canon, a Casio and a Sony). Each offers a menu option to reset the file number, but in each case the default is NOT to reset. Keeping that default setting, I went through these steps:

1. Take a picture. Note that the file name is IMG_0508.JPG.

2. Remove the memory card; replace it with a different card.

3. Erase and reformat the new memory card.

4. Take another picture. The file name is IMG_0509.JPG.

I don’t dispute that you can set up the camera to start at 0001 each time the card is erased, but that’s not the default behavior on any of the cameras I have at hand.

A few questions:

1. Does the camera saving into different folders ever come into play in the sequencing of the file name?

2. Could some of the frequency of food and vehicles be because of the prominence of photos for commerce and advertising (restaurants and car sales)?

3. How is your assumption of randomness affected by the naming of photos? (i.e. is a better web-developer likely to name his photos better and therefore be exempt from the IMG_nnnn schema?)

Thanks for the data. We are about to start our chapter on power/exponential/log fitting, so we’ll see how they like the data set.

Thanks for the post. In my opinion, it’s a good example of bottom-up data a thing we are not accustomed to yet. Just a possible further bias on the randomization: I suspect that Google puts some bias on searches based on the user (if she is logged on the browser), the location, etc. So, maybe, your set of IMG_1134s is somehow different from what I could have got here in Italy.

@ Fabrizio Iozzi. Good point. When I ran my searches, I did so from an account that wasn’t logged in to Google, using a browser from which I had cleared all cookies. But my IP number still conveys geographic (and probably other) information. These days, we each see our own private web.

The counter rotates around and resets on Canon point and shoots and Nikon dslrs. An interesting thing would be to search Flikr using metadata and look at the shutter count (which has enough bits to not reset, I think)

I’d be curious if the same holds true for smartphones. My impression (no data) is that people take more pictures over time with smartphones rather than less.

First they don’t really consider it a camera. Then they find out how convenient it is. Then they start posting to facebook, instagram, pinterest. They start getting photo apps (9 million downloads for Camera+). The start using it for things they might not use other cameras for like taking a picture of a flyer to remember the date etc..

I don’t know if there’s a way to figure any of that out though.

That’s a fascinating study. I suspect part of the falloff at higher numbers could be the result of getting a new camera and starting over. But it is fascinating that the curve seems to fit y = e^-x.

One thing to consider: I recently got a Nikon CoolPix. It names photos “DSCNnnnn.JPG”, with an occasional “FSCNnnn.JPG”.

Google/Images(dscn) comes up with a list, including “index of dcsn”, with “About 6,650,000 results (0.27 seconds)”. It turns out that the word “index” is in each title.

‘dscn1134′: “About 103,000 results” - but: it prompts “Did you mean: dscn 1134?” , which gives “About 190,000 results”. Completely different - and the file names are without the space.

‘dscn0001′: About 245,000 results . (There is a DSCN lab at U Maryland.)

‘dscn0000′: “About 155 results”,

One problem I faced was saving photos to disk. It took a while before I noticed that my earlier photos were disappearing. Now I make a folder for each save.

On a societal note, every now and again we read of someone who’s been embarrassed by having their photos and videos from photo sites and YouTube make it to the front pages. One commentor noted that it’s not Big Brother who’s watching every move, it’s us.